by Tim Queeney

Tim Queeney, author of Rope: How a Bundle of Twisted Fibers Became the Backbone of Civilization, shares with The History Reader how rope played a pivotal role in Colonial America’s acts of tarring and feathering before it fell into gradual disuse in the nineteenth century.

In Colonial America, especially during the era of the American Revolution, the brutal practice of tarring and feathering was used by revolutionary groups like the Sons of Liberty to humiliate government officials and loyalists. Ropewalks, the long buildings where rope was manufactured, provided a ready supply of warm pine tar for revolutionary mobs.

Tar was always on hand at ropewalks because rope twisted from natural fibers like hemp and flax was prone to rot when wet. And since much of the output of ropewalks in port cities like Boston was used on board sailing ships as standing and running rigging, it was necessary to make the new rope water resistant by dredging it through vats of heated tar.

Boston, for example, had multiple ropewalks in the colonial era, producing rope for both colonial use and for the Royal Navy. In 1722, for example, Boston had four of these long buildings. One of them, built by a ropemaker named John Harrison, whom city officials had recruited to come to town in 1666, stretched 984 feet. By 1788, five years after the end of the revolution, the number of ropewalks had increased to 14 and the job of ropemaker was the city’s single largest occupation.

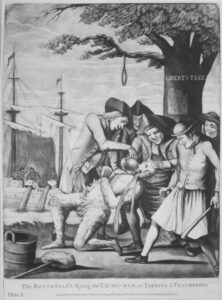

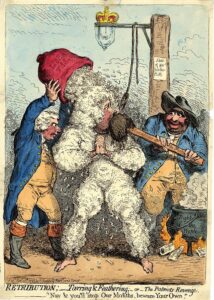

While tarring and feathering amused revolutionary mobs, for the victim, the practice was humiliating and painful. The victim was either stripped to the waist or entirely covered with sticky pine tar and then liberally doused with feathers. Victims were sometimes further made to ride on a rail and carried around the town for maximum humiliation.

As bad as it was, however, there are no records of any persons who were subjected to the torture dying from it. Unlike coal tar, which is heated to 300° F to liquify it, pine tar is usually only brought to 140°. So, while capable of producing great discomfort, it was generally not a fatal experience.

There was a notably savage 1775 case of a landowner in Georgia, Thomas Brown, who was tarred and feathered and beaten by a revolutionary mob for his refusal to join the cause of independence. (Since the states of North and South Carolina and Georgia produced thousands of barrels of pine tar every year, there was plenty of tar available.) In Brown’s case, his skull was fractured by the blow from a rifle butt and the tar on his legs was set alight, badly burning Brown’s feet. The crazed mob even tried to scalp him. Somehow, he survived the ordeal, which had the opposite effect intended. Brown had previously been neutral on independence, but the attack pushed him toward the loyalist cause. After recovering Brown organized a loyalist militia unit called The King’s Rangers to harry revolutionaries in Georgia.

Two years before the attack on Thomas Brown, a customs official by the name of John Malcom had the distinction of being tarred and feathered twice by angry gangs. As Alfred Fabian Young recounts in his 1999 book The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, Malcolm was a difficult man with “a fiery temper” who was fervently devoted to enforcing British government taxation policy. “Malcom had already acquired an odious reputation…. A Bostonian, he had been a sea captain, an army officer, and recently an employee of the customs service.” In colonial times it was a regular practice for American sailors to bring in a bottle or two of liquor when returning home from a voyage. Malcom was a stickler for the letter of the law, however. Young notes, “As a customs informer, he was known to have turned in a vessel to punish sailors for petty smuggling.”

It seems that Malcom’s reputation preceded him, and in November 1773, a gang of some thirty sailors took their revenge. The act of aggression, however, was characterized at the time by the Boston Gazette as the sailors having “genteely tarr’d and feather’d” Malcolm because they allowed him to keep his clothes on before dousing him with tar and applying the feathers.

The situation was different in early 1774 when Malcolm found himself on the wrong end of a Boston liberty gang. It began on January 25, 1774 when Malcolm had a run-in with a shoemaker named George Robert Twelves Hewes. The tradesman had come to the aid of a boy who Malcolm was threatening with his cane. When they argued and Hewes made reference to Malcolm’s tarring and feathering in Portsmouth, Malcolm became incensed and struck Hewes on the head. Word of the attack spread, and by evening, a mob formed outside Malcolm’s house. He was dragged out into the street and stripped to “buff and breeches.” They then gave him “a modern jacket” — the Boston Gazette’s euphemism for a tarring and feathering. It didn’t end there. Malcolm was put in a cart and a rope was rigged with a noose to threaten him with hanging. Finally, the cart was hauled to the Boston Liberty Tree where, in an echo of the Boston Tea Party from a month before, tea was forced down Malcolm’s throat until he vomited.

Tarring and feathering incidents still occurred into the nineteenth century, but the practice gradually fell into disuse. Perhaps partly because ropemaking with its vats of bubbling pine tar became increasingly consolidated into industrial facilities like the Plymouth Cordage Company in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Ropemaking contributed to this brutal practice, but was not wholly culpable — pillow and mattress

Tim Queeney is the editor of Ocean Navigator, a magazine for offshore voyager. Tim’s work has appeared in Professional Mariner, American History, and Aviation History. He has had short stories published in the crime anthology Landfall, Best New England Crime Stories 2018 and in the speculative anthology A Land Without Mirrors. Tim lives in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, with his wife and a rescue dog, Frankie. A lifelong sailor, he teaches celestial navigation, radar navigation, and coastal piloting ashore — where he tied plenty of knots and handled many a rope.