by Anne Sinclair; Translated from the French by Shaun Whiteside

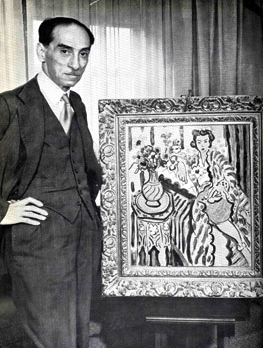

Paul Rosenburg

Rue la Boétie Number 21. I’ve passed by it hundreds of times. My mother liked to show me the 1930s façade with its stone arches. I’d noticed various shops on that street—ice cream, pizza—but I’d never stopped to take a closer look. Now, seventy years after my grandfather Paul Rosenberg had left the premises, I wanted to see the building for myself. I couldn’t imagine that three years later I would unveil a plaque on this very building that I had not yet entered. Today it’s an office of the Veolia Environmental Services company. I call them up: “My grandparents used to live there. I’d love to take a look around, really just a look. I don’t want to disturb you … It was before the war, I’m sure there are few traces left … Of course I understand if it’s not possible.” I detected the ambivalence in my own voice. It was almost as if I worried that they might actually let me in. They did. Why would they resist?

Image is in the public domain via TheGuardian.com

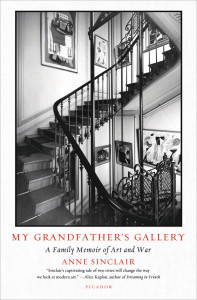

So one Wednesday in April 2010 off I went to Veolia, to 21 rue La Boétie, where I begin my story. Touched by my curiosity and possibly a bit incredulous that it’s taken me to the age of sixty to set foot in the building where my grandfather’s gallery was located, my hosts graciously show me around. The hallway has been divided, and there are white stucco columns with Corinthian capitals, which I find a bit tasteless. Are they original? And a black-and-white damier marble floor. It’s all been redesigned, modernized, the rooms, the spaces. There are spotlights affixed to the ceiling. The staircase with its old-fashioned banisters leading to the upper floors seems unchanged. Lots of Fernand Léger’s and André Masson‘s paintings used to hang on the walls of this interior stairway, which led to my family’s private apartments: the one belonging to my grandparents and their children, then the one to my great-grandmother, Paul Rosenberg’s mother, Mathilde Rosenberg. Of course no paintings now hang in this stairway, which leads to various offices. The overall impression is dreary. Yet the elevator is modern, surely in compliance with health and safety regulations. The rattling old cage of another age is gone. The stairway within the gallery, the one with the cast-iron banister, seems to have retained its original look, from the 1930s, when my grandfather did some elaborate renovations. The floor is patterned with marble mosaics made with yellow stones. But there’s no way of telling exactly where the mosaic plaques went, the ones designed by Georges Braque, who also supervised their installation. Above the stairs were arches, replicas of the ones outside, adorned with pieces of mirrored glass. I’m in the lower of the two exhibition halls, the one that appears in so many of the photographs I’ve seen of my grandfather situated in his domain. All the exhibitions at rue La Boétie were held in this large room. A month of Braque, another of Henri Matisse, a third of Pablo Picasso. It is now a boardroom for Veolia executives. The fine oak parquet floor is still there, and I immediately recognize the wood paneling, which I’ve seen in the photographs, as well as the glass ceiling with its little star-shaped windows, which, as in other galleries of the time, diffused the light so as to soften the hard edges of cubist painting. If I half closed my eyes I could see them, those big paintings from the 1920s and 1930s, hanging on the walls. Soon after, those masterpieces would be replaced by portraits of the head of the Vichy government, Marshal Philippe Pétain.

In 1927 E. Tériade, a famous critic and art publisher of Greek descent, described the Galerie Rosenberg in “Feuilles volantes,” the monthly supplement of the influential journal Cahiers d’art: “We are introduced into a huge room, high-ceilinged, bare walls, naked light, a room in which sober brown curtains weigh down on the collection, in which two solitary armchairs upholstered with dark velvet reach toward you like two grand inquisitors; no, they’re not reaching toward you, they’re going for your throat, as masterpieces do. Hurricanes of solitude, of austerity, pass through the room … Paul Rosenberg: he’s dressed in black. He has the anxious face of an ascetic or a passionate businessman.”1 Here’s another description of the setting, particularly interesting when you consider that the author is the notorious, extreme-right-wing writer Maurice Sachs, who later defined himself as a Jew, a homosexual, and a collaborator before being killed by a bullet to the back of the head by the Germans in whose service he had worked: “His grand seigneur bearing was part of his particular genius … You step into Rosenberg’s gallery as if entering a temple: the deep leather armchairs, the walls lined with red silk, would lead you to think you were in a fine museum … He knew how to cast an extraordinary light on the painters he took under his wing. His knowledge of painting was deeper than that of his colleagues, and he had a very sure sense of his own taste.” Paul Rosenberg , who had taken over his father’s gallery with his brother, Léonce, in 1905, decided to set up on his own in 1910 and moved alone to 21 rue La Boétie, in the Eighth Arrondissement of Paris. Nineteenth-century works were shown on the mezzanine; contemporary art, on the ground floor. If visitors were unsure about Braque or Léger, Paul Rosenberg invited them upstairs to see softer-contoured works by Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, or Auguste Rodin. He hoped they might buy some of these, which would allow him to support his unknown friends, such as Picasso or Marie Laurencin, the muse of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1913 she became the first artist to sign an exclusive deal with Paul Rosenberg, an arrangement that stood until 1940. She was joined by Picasso in 1918, Braque in 1923, Léger in 1926, and Matisse in 1936.

Image is in the public domain via Passouline.blog.lemonde.fr

In 1912, almost as soon as he had moved in, Paul sent out an announcement just as anyone opening a shop might do, describing his new venture: “I will shortly be opening new modern art galleries at 21 rue La Boétie, where I plan to hold periodic exhibitions by the masters of the nineteenth century and painters of our own times. In my view, however, the shortcoming of contemporary exhibitions is that they show an artist’s work in isolation. So I intend to hold group exhibitions of decorative art … Not only do I plan to offer my spaces for free, I shall not take a percentage in the event of a sale. For each exhibition I shall publish at my own expense a catalog of the paintings, sculptures, furniture, etc.” The critic Pierre Nahon stresses Paul’s desire to establish a connection between French painting of the past and the modernist trends of the twentieth century, noting that in the late 1930s Paul had on his walls and in his inventory a collection of Géricault, Ingres, Delacroix, Courbet, Cézanne, Manet, Degas, Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, ToulouseLautrec, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Le Douanier Rousseau, Bonnard, Laurencin, Modigliani, and Matisse. “The gallery,” Nahon writes, “is becoming an essential meeting place for everyone who wants to follow the development and the work of the innovative painters.” My own research is centered on an attempt to conjure the grandfather I barely knew. And to summon up the riches heures of the thirties and the grim ones of the forties that are integral to his story.

Read more about the story of Nazi looted art on TheHistoryReader.com

My grandfather had great difficulty regaining possession of his gallery after the war. The state had confiscated the building from the collaborators in August 1944 and made it the headquarters of the Saint-Gobain construction company, before finally returning the building to my grandfather. By then it had endured the sinister events that I am about to relate, events with which my grandfather could never make peace. Paul Rosenberg finally sold 21 rue La Boetie in January 1953. He was determined never again to live in that place, its basement filled with propaganda from the darkest years, its rooms still haunted by the ghosts of the occupation. For a long time the building was home to the French General Information Service, Renseignements Généraux, the French police intelligence service, and the secrets of the Republic were buried with the secrets of the collaborators.

Anne Sinclair is the author of MY GRANDFATHER’S GALLERY: A Family Memoir of Art and War Paul Rosenberg’s granddaughter and one of France’s best-known journalists. For thirteen years she was the host of 7 sur 7, a weekly news and politics television show for which she interviewed world figures of the day, including Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Madonna. The editorial director of Le Huffington Post (France), Sinclair has written two bestselling books on politics.