by Jerry Barca

In early December 1984, two days after the NY Giants lost their tenth game of the season, Lawrence Taylor sat down to lunch to deal with Donald Trump. The real estate magnate had recently purchased the USFL’s New Jersey Generals. He wanted to gauge Taylor’s interest in signing with the upstart league.

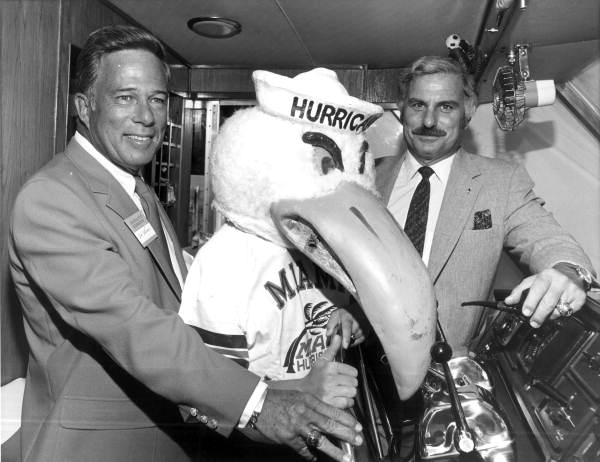

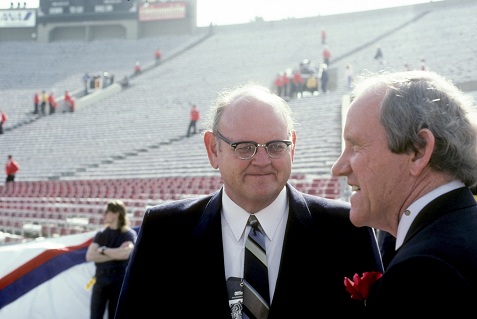

While LT flirted with Trump, NY Giants general manager George Young contemplated a coaching change. He called Howard Schnellenberger, the head coach at the University of Miami. Young had served as Schnellenberger’s offensive line coach with the Baltimore Colts in 1973 and for part of the ’74 season.

Young and Trump battle for Schnellenberger

After the conversation ended with Young, Schnellenberger called his agent, Robert Fraley, a former Alabama quarterback who died in a plane crash with his client, golfer Payne Stewart, in 1999. When Schnellenberger spoke to him, Fraley was already in the New York City area, attempting to strike a deal with Trump for Schnellenberger to coach the Generals. Once Fraley heard about the NY Giants’ interest in Schnellenberger, the agent knew he had to let one of his clients know. That client was Bill Parcells.

Parcells resented Young’s covert maneuvering. The NY Giants coach called one of his mentors, the Raiders’ Al Davis, the NFL’s renegade owner. Davis and Parcells met when Parcells played for Davis in a college all- star game in 1964.

Parcells said Davis gave him owner ship’s perspective. “You have to be able to put yourself in the position of the owners and what they’re looking at. And what they’re seeing and why things are the way they are— that’s why you’re in jeopardy,” Parcells said, recalling what Davis told him in the conversation.

CBS announces the NY Giants are in talks with Howard Schnellenberger

Before the phone call ended, Davis closed the conversation, telling Parcells he’d handle the situation. Davis gave the scoop to Jimmy “the Greek” Snyder, a lead analyst on CBS’s The NFL Today. Years before ten hours of Sunday pregame coverage spread itself across four TV networks, The NFL Today was the leading program for football information. Snyder took to the airwaves outing the NY Giants’ talks with Schnellenberger, who was getting Miami ready to play Nebraska for the national championship. Snyder also backed the idea of giving Parcells another year on the job.

The NY Giants lost 17–12 to Seattle that Sunday. A potential game-winning touchdown pass was called back on a holding penalty. Young refused to talk to the media about Snyder’s on- air comments. That week, Parcells and Young met to discuss his status. Parcells asked if he would be back in 1984. Young said that discussion would have to wait until aft er the season.

Lawrence Taylor accepts a $1 million interest-free loan from Donald Trump

On Wednesday of that week, LT accepted a $1 million interest-free loan from Donald Trump. The money was part of a deal that put Taylor in a personal services agreement with Trump and called for the linebacker to play for the New Jersey Generals in 1988, after his NY Giants contract expired. Excluding the $1 million loan, the deal was worth $2.7 million over four years. The personal services aspect called for Taylor to immediately start performing promotional tasks for Trump’s real estate operations.

“There was no way that my father was going to allow him to walk out the door and go play for somebody else,” said John Mara, who at the time was a twenty-nine-year-old attorney at Shea & Gould, the New York City law firm representing Trump.

The NY Giants renegotiated LT’s deal within a month. The organization more than tripled his base salary for the next season, increasing it from $190,000 to $650,000. The NY Giants added years to the contract and escalating base pay, which would reach $1 million in 1988. Th e franchise also added its own $1 million interest- free loan. In order to buy out his contract with Trump, LT gave back the original $1 million loan, and Trump was paid $750,000 over the next five years.

An end to a bad year

While LT was agreeing to a deal with Trump to leave the NY Giants, Parcells had to get ready for the Washington Redskins and make funeral arrangements for his mother. Ida Parcells died in mid-December. Charles Parcells, Bill’s father, could not attend the funeral. He stayed in the hospital, still recovering from the bypass surgery.

The day after Bill attended services for his mother, the NY Giants lost the season finale in Washington. Parcells’s first season as an NFL head coach had come to an end. His team posted a dismal 3–12–1 record.

Big Blue finished the year with a league- high twenty- five players on injured reserve. Brunner, Parcells’s pick as the number- one quarterback, finished the season at number two on the depth chart. He threw 22 interceptions and nine touchdowns in 13 games. Overall, the team tallied 58 turnovers. The NY Giants handed the ball over to their opponents more than three and a half times a game. They racked up 113 penalties, which accounted for 1,020 lost yards. The defense tailed off, too, giving up 21.7 points per game, dropping the G- Men from eighth in the league in ’82 to sixteenth.

Young had gone back to speak to Schnellenberger again. Schnellenberger’s deal with Trump and Generals never materialized, but Young couldn’t get Schnellenberger to commit to coaching the NY Giants in ’84.

“I remember George talking to him and then coming back to us,” John Mara said.

“I can’t get him this year, but I can get him next year. So let’s give Parcells one more year,” Young told ownership.

“Had Schnellenberger said yes, Parcells would’ve been fired at the end of the ’83 season, something I know Bill was bitter about for years to come,” Mara said.

Parcells reevaluates his performance

A few weeks after the season, Parcells knew he would at least be the head coach at the start of the next season. The overtures to Schnellenberger irritated him. At the same time, he knew he did a miserable job that first year. He knew he had to change.

When Parcells evaluated his own performance, he saw he wasn’t the head coach he wanted to be. He was friendly with players. As a coordinator, a cozy relationship with players didn’t hurt him. As a head coach, it did. He saw poor habits and let them slide. Veterans players, who by virtue of their experience were role models, weren’t held accountable.

“I just don’t think I was assertive enough, demanding enough.”

“I decided to stay and finish what I came to New York for with Coach Perkins”

In January, linebackers coach Bill Belichick was offered a position with the Minnesota Vikings. Belichick visited Minnesota, where Les Steckelhad become the head coach and Floyd Reese was set to serve as the defensive coordinator. Belichick discussed the opportunity with Parcells. The looming backdrop to a conversation like this one was the lack of security with the NY Giants. Sure, Parcells and his staff would start 1984, but that was the only guarantee. There were no reassurances that they would be with the NY Giants for the long term.

“Bill did not discourage me from taking the job,” Belichick said. “I decided to stay and finish what I came to New York for with Coach Perkins—to produce a winner in New York. The deck appeared to be stacked against us, but I was committed to Bill, Ernie [Adams], and the organization to help put a good team together.”

JERRY BARCA is the author of BIG BLUE WRECKING CREW: Smashmouth Football, a Little Bit of Crazy, and the ’86 Super Bowl Champion New York Giants and journalist. His writing has been published in The New York Times, SI.com, ESPN.com, and he is a regular contributor to Forbes. He is the author of Unbeatable: Notre Dame’s 1988 Championship and the Last Great College Football Season and he produced the documentary film Plimpton!, which was a New York Times critic’s pick. Barca is a graduate of Seton Hall Prep with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Notre Dame and a master’s from Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and their four children.