by Ian Plenderleith

NASL Soccer

Everyone knows that the New York Cosmos was the baddest, sexiest team in the old North American Soccer League, right? They had Pelé, Giorgio Chinaglia and Franz Beckenbauer. They were owned by Warner Communications, hung out in Studio 54 with Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol and Muhammed Ali, and flew to games in a private jet. They filled the Meadowlands in New Jersey – an NFL stadium – to capacity. They scored a ton of goals, and they won the most championships. Who could dispute that they were NASL Soccer’s flagship team, the franchise that propelled the league to global notoriety, and whose excesses catalysed its early demise?

All true, yet the Cosmos were as contrived as anything that came out of Warhol’s factory. Warner bought the ramshackle, semi-pro team in 1972 and by the end of the decade had molded it into a sporting glamour vehicle by paying high wages to aging world superstars. For the entertainment company, the Cosmos were another promotional corporate tool, an archetypal forerunner of the cash-loaded soccer monoliths like Real Madrid and Manchester City that dominate the global sport today. They were a brilliant, dazzling and fascinating team, but below the surface that image of coolness was just media-generated fakery.

No, the coolest team in NASL soccer was not the Cosmos. The coolest team in the league came from the unfashionable, frozen north. Like all cool things, they happened almost by accident. They were called the Minnesota Kicks.

The Kicks were founded in late 1975 by a retail entrepreneur, Jack Crocker, who watched an NASL soccer game in his native Portland with 30,000 other people and liked both what he saw and what he felt amidst the enthusiastic crowd. Back in Minnesota he assembled a group of investors from the grocery business and persuaded them to move a failing NASL soccer franchise from Denver, Colorado, to ‘The Met’ in Bloomington – the 48,000-capacity home to the Twins and the Vikings. On opening day in May 1976, the larger than expected crowd caused repeated delays to the kick-off, so Crocker decided to let the last 3,000 fans in for free, unwittingly landing a huge PR coup. The official gate of 17,000 at the 4-1 win over San Jose was probably much higher.

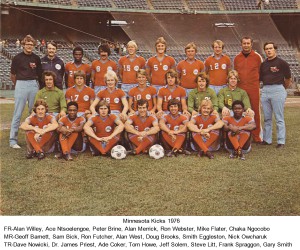

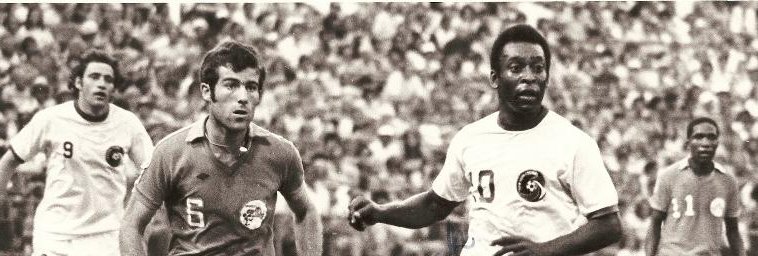

Crowds for the following games flattened out a little but the team – with a roster made up of eleven Englishmen, six Americans, two South Africans and a Nigerian – kept winning. The Kicks’ fifth home game was against the Cosmos, and all of a sudden there were 46,000 people in The Met watching Pelé and Chinaglia, who scored the winning goal for the visitors. Under coach Freddie Goodwin the Kicks propagated attacking soccer, with English strikers Alan Willey and Ron Futcher scoring 30 goals between them in 1976, supported by South African midfield genius Ace Ntsoelengoe. The three players are second, fourth and eighth respectively on the NASL all-time scorers’ chart.

Yet neither the players nor the ownership secured the Kicks’ place in NASL soccer mythology. It was the crowds, and what they did in and around the stadium before and after games. One writer at the time compared the atmosphere to a Grateful Dead concert. At Kicks’ games “the Woodstock generation and their younger brothers and sisters stand around in the Met Stadium parking lot sharing bread, a bottle of wine and a joint,” wrote Jon Bream in the Minneapolis Star. “They toss Frisbees and frolic in the sun.” Parking was free (another stroke of marketing savvy by the owners), and game tickets were cheap at $2.50. There were girls too, some wearing t-shirts that said ‘Soccer Foxes’. All of a sudden for young people in Minnesota, pro soccer games were the best place to party.

Things continued to go well on the field as the Kicks qualified for the playoffs every year. The well-oiled crowds were raucous, and in the words of team captain Alan Merrick, “Nobody came to that stadium with a chance.” On August 14, 1978, the Kicks hammered the Cosmos 9-2 in front of 45,863 delirious fans in a playoff game. It couldn’t get much better than that (in fact it didn’t – the Cosmos went through after winning the return game in NJ 4-0, and then a deciding mini-game).

The Kicks conjured huge crowds, a successful team, compelling rivalries with both the Cosmos and the Tulsa Roughnecks, and the cult of the tailgate, but the figures didn’t add up. After five loss-making years, Crocker and his associates sold the team because in 1980 they had lost half a million dollars, and crowds were falling. A posh but vague Englishman called Raph Sweet was the ostensible buyer, though the team’s former players claim he was just a frontman for some dubious British businessmen. Within a year the club had folded, and its last home game in late 1981, a 0-3 loss to Fort Lauderdale, was played in front of just under 12,000 fans.

“The demise of the Kicks led to the demise of the League,” claims Merrick. Other owners thought that if a buoyant team like the Kicks couldn’t make it, then there was no hope. The old NASL folded completely in 1984, but English native Merrick still lives close to Minneapolis. The day I interviewed him at his home in early 2014, the mail-man delivered a package from Virginia – inside was a 1970s Minnesota Kicks shirt that the sender wanted Merrick to sign and return. “I get stuff like this all the time,” he says with a smile.

Forty years after the Kicks, Minnesota United FC of the re-formed, second-tier NASL soccer is close to moving to Major League Soccer and bringing the pro game back to the Twin Cities. In many ways that’s thanks to the players who seduced (and were seduced by) a city and, like Merrick, never left. It’s also because a generation of fans fondly remembers getting stoned or drunk and falling in love outside The Met.

IAN PLENDERLEITH is a British soccer writer, author of Rock ‘N’ Roll Soccer and journalist who has lived in the United States for the past 15 years. Author of the critically acclaimed short story collection For Whom The Ball Rolls, he has been writing about soccer in the UK, Germany and the US for the past twenty years for publications such as The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, Soccer America, Prospect and When Saturday Comes.