Wcag Heading

by Mark Kram

Wcag Heading

Wcag Heading

“Lawdy Lawdy He’s Great” – (Ali Frazier III) Sports Illustrated Oct 13, 1975

Across the ring Joe Frazier was wearing trunks that seemed to have been cut from a farmer’s overalls. He was darkly tense, bobbing up and down as if trying to start a cold motor inside himself. Hatred had never been a part of him, but words like “gorilla,” “ugly,” “ignorant”— all the cruelty of Ali’s endless vilifications— had finally bitten deeply into his soul. He was there not seeking victory alone; he wanted to take Ali’s heart out and then crush it slowly in his hands. One thought of the moment “LAWDY, LAWDY, HE’S GREAT” 65 days before, when Ali and Frazier with their handlers between them were walking out of the Malacañang Palace, and Frazier said to Ali, leaning over and measuring each word, “I’m gonna whup your half- breed ass.”

By packed and malodorous jeepneys, by small and tiny taxis, by limousine and by worn- out bikes, twenty- eight thousand had made their way into the Philippine Coliseum. The morning sun beat down, and the South China Sea brought not a whisper of wind. The streets of the city emptied as the bout came on public television. At ringside, even though the arena was air- conditioned, the heat wrapped around the body like a heavy, wet rope. By now, President Ferdinand Marcos, a small, brown derringer of a man, and Imelda, beautiful and cool as if she were relaxed on a palace balcony taking tea, had been seated.

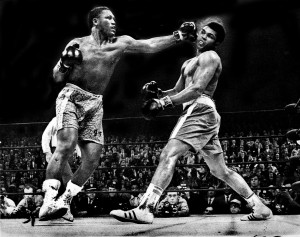

True to his plan, arrogant and contemptuous of an opponent’s worth as never before, Ali opened the fight flat- footed in the center of the ring, his hands whipping out and back like the pistons of an enormous and magnificent engine. Much broader than he has ever been, the look of swift destruction defined by his every move, Ali seemed indestructible. Once, so long ago, he had been a splendidly plumed bird who wrote on the wind a singular kind of poetry of the body, but now he was down-to-earth, brought down by the changing shape of his body, by a sense of his own vulnerability, and by the years of excess. Dancing was for the ballroom; the ugly hunt was on. Head up and unprotected, Frazier stayed in the mouth of the cannon, and the big gun roared again and again.

Frazier’s legs buckled two or three times in that first round, and in the second he took more lashing as Ali loaded on him all the meanness that he could find in himself. “He won’t call you Clay no more,” Bundini Brown, the spirit man, cried hoarsely from the corner. To Bundini, the fight would be a question of where fear first registered, but there was no fear in Frazier. In the third round Frazier was shaken twice and looked as if he might go at any second as his head jerked up toward the hot lights and the sweat flew off his face. Ali hit Frazier at will, and when he chose to do otherwise, he stuck his long left arm in Frazier’s face. Ali would not be holding in this bout as he had in the second. The referee, a brisk workman, was not going to tolerate clinching. If he needed to buy time, Ali would have to use his long left to disturb Frazier’s balance.

A hint of shift came in the fourth. Frazier seemed to pick up the beat, his threshing- blade punches started to come into range as he snorted and rolled closer. “Stay mean with him, champ!” Ali’s corner screamed. Ali still had his man in his sights and whipped at his head furiously. But at the end of the round, sensing a change and annoyed, he glared at Frazier and said, “You dumb chump, you!” Ali fought the whole fifth round in his own corner. Frazier worked his body, the whack of his gloves on Ali’s kidneys sounding like heavy thunder. “Get out of the goddamn corner,” shouted Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer. “Stop playing,” squawked Herbert Muhammad, wringing his hands and wiping the mineral water nervously from his mouth. Did they know what was ahead?

Came the sixth, and here it was, that one special moment that you always look for when Joe Frazier is in a fight. Most of his fights have shown this: you can go so far into that desolate and dark place where the heart of Frazier pounds, you can waste his perimeters, you can see his head hanging in the public square, maybe even believe that you have him, but then suddenly you learn that you have not. Once more the pattern emerged as Frazier loosed all the fury, all that has made him a brilliant heavyweight. He was in close now, fighting off Ali’s chest, the place where he has to be. His old calling card— that sudden evil, his “LAWDY, LAWDY, HE’S GREAT” left hook— was working the head of Ali. Two hooks ripped with slaughter house finality at Ali’s jaw, causing Imelda Marcos to look down at her feet, and the president to wince as if a knife had been stuck in his back. Ali’s legs seemed to search for the floor. He was in serious trouble, and he knew that he was in no-man’s-land.

Whatever else might one day be said about Muhammad Ali, it should never be said that he is without courage, that he cannot take a punch. He took those shots by Frazier and then came out for the seventh, saying to him, “Old Joe Frazier, why I thought you were washed- up.” Joe replied, “Somebody told you all wrong, pretty boy.”

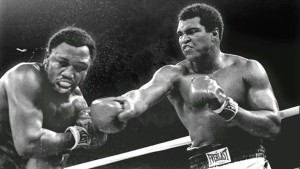

Frazier’s assault continued. By the end of the tenth round it was an even fight. Ali sat on his stool like a man ready to be staked out in the sun. His head was bowed, and when he raised it, his eyes rolled from the agony of exhaustion. “Force yourself, champ!” his corner cried. “Go down to the well once more!” begged Bundini, tears streaming down his face. “The world needs ya, champ!” In the eleventh, Ali got trapped in Frazier’s corner, and blow after blow bit at his melting face, and flecks of spittle flew from his mouth. “Lawd have mercy!” Bundini shrieked.

The world held its breath. But then Ali dug deep into whatever it is that he is about, and even his severest critics would have to admit that the man- boy had become finally a man. He began to catch Frazier with long right hands, and blood trickled from Frazier’s mouth. Now Frazier’s face began to lose definition; like lost islands reemerging from the sea, massive bumps rose suddenly around each eye, especially the left. His punches seemed to be losing their strength. “My God,” wailed Angelo Dundee. “Look at ’im. He ain’t got no power, champ!” Ali threw the last ounces of resolve left in his body in the thirteenth and fourteenth. He sent Frazier’s mouthpiece flying into the press in the thirteenth and nearly floored him with a right in the center of the ring. Frazier was now no longer coiled. He was up high, his hands down, and as the bell for the fourteenth sounded, Dundee pushed Ali out saying. “He’s all yours!” And he was, as Ali raked him with nine straight right hands. Frazier was not picking up the punches, and as he returned to his corner at the round’s end, the Filipino referee guided his great hulk part of the way.

“Joe,” said his manager, Eddie Futch, “I’m going to stop it.”

“No, no, Eddie, ya can’t do that to me,” Frazier pleaded, his thick tongue barely getting the words out. He started to rise.

“You couldn’t see in the last two rounds,” said Futch. “What makes ya think ya gonna see in the fifteenth?”

“I want him, boss,” said Frazier. “Sit down, son,” said Futch, pressing his hand on Frazier’s shoulder. “It’s all over. No one will ever forget what you did here today.”

MARK KRAM, JR. is the author of Great Men Die Twice and Like Any Normal Day, which received the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing. His feature articles have won the Sigma Delta Chi award from the Society of Professional Journalists, been awarded top honors by the Associated Press for three consecutive years, and been published six times in The Best American Sports Writing Anthology. Kram lives in New Jersey with his wife and two daughters.

Mark Kram Lawdy Lawdy He’s Great.