by Philip Jett

It was November 30, 1955, and the Cold War was raging. The U.S. had stockpiled 2,422 atomic bombs while the Soviets had only about 200, though more than ample to annihilate the United States. With the Soviet Union fewer than 2,000 miles away, the U.S. formed the Continental Air Defense Command (CONAD) to provide a timely defense system against intercontinental ballistic missiles fired by the Soviets over the North Pole and Canada that could strike the United States. CONAD’s command post was in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Colonel Harry W. Shoup directed its Combat Operations Center. He reported directly to four-star general Earle “Pat” Partridge, who in turn reported directly to President Eisenhower.

The United States held the advantage not only in atomic ballistic missiles, but in department stores, with chains such as J.C. Penney, Montgomery Ward, Macy’s, and Sears showcasing good ol’ American capitalism throughout the land. For almost thirty years, retired Brigadier General Robert Wood served as president and chairman of the largest retail chain at that time, Sears, Roebuck and Co., placing more than 700 of its department stores across the United States as part of an economic strategy, not a defensive one. Yet, General Wood’s strategy did enable Sears to provide U.S. citizens with a protective blanket of goods that soon would be shipped to all corners of the nation by means of Eisenhower’s National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

The United States held the advantage not only in atomic ballistic missiles, but in department stores, with chains such as J.C. Penney, Montgomery Ward, Macy’s, and Sears showcasing good ol’ American capitalism throughout the land. For almost thirty years, retired Brigadier General Robert Wood served as president and chairman of the largest retail chain at that time, Sears, Roebuck and Co., placing more than 700 of its department stores across the United States as part of an economic strategy, not a defensive one. Yet, General Wood’s strategy did enable Sears to provide U.S. citizens with a protective blanket of goods that soon would be shipped to all corners of the nation by means of Eisenhower’s National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

And so it was on that night of November 30 that Colonel Shoup sat at his desk overseeing his minions manning the consoles inside a 15,000-square foot fortified concrete blockhouse at Ent Air Force Base (prior to being moved under Cheyenne Mountain). Atop his desk sat an ordinary black telephone with an unlisted number and an ominous red phone that connected him to General Partridge via a dedicated line encased in lead to protect it from an atomic blast. Opposite the consoles stood a massive 22’ long by 30’ high plexiglass map of North America and the polar regions on which spotters wrote coordinates of ships and aircraft that could not be immediately identified (somewhat like the “big board” of Dr. Strangelove movie fame).

And so it was on that night of November 30 that Colonel Shoup sat at his desk overseeing his minions manning the consoles inside a 15,000-square foot fortified concrete blockhouse at Ent Air Force Base (prior to being moved under Cheyenne Mountain). Atop his desk sat an ordinary black telephone with an unlisted number and an ominous red phone that connected him to General Partridge via a dedicated line encased in lead to protect it from an atomic blast. Opposite the consoles stood a massive 22’ long by 30’ high plexiglass map of North America and the polar regions on which spotters wrote coordinates of ships and aircraft that could not be immediately identified (somewhat like the “big board” of Dr. Strangelove movie fame).

On that same day, the Sears store in Colorado Springs placed an advertisement in the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph newspaper that read: Hey, Kiddies! Call me direct on my Merry Xmas telephone. Just dial ME 2-6681. Kiddies be sure and dial the correct number.

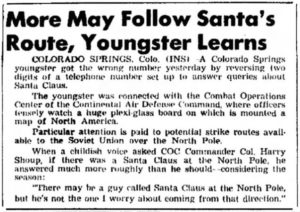

As one would expect, a little boy attempting to dial Santa reversed two digits and the Mountain States Telephone Company connected him not to Sears’s North Pole in Colorado Springs, but to the desk telephone of Colonel Shoup, inside CONAD’s fortified blockhouse. When the boy timidly asked if the gruff-voiced Shoup was Santa at the North Pole, the brash colonel replied, “There may be a guy named Santa Claus at the North Pole, but he’s not the one I worry about coming from that direction,” and clanked down the telephone receiver. (Later, Shoup and his family good-naturedly embellished the story, creating the myth that Shoup embraced the role of Jolly Ol’ St. Nick and fielded several calls from children on the clandestine red phone that night).

As one would expect, a little boy attempting to dial Santa reversed two digits and the Mountain States Telephone Company connected him not to Sears’s North Pole in Colorado Springs, but to the desk telephone of Colonel Shoup, inside CONAD’s fortified blockhouse. When the boy timidly asked if the gruff-voiced Shoup was Santa at the North Pole, the brash colonel replied, “There may be a guy named Santa Claus at the North Pole, but he’s not the one I worry about coming from that direction,” and clanked down the telephone receiver. (Later, Shoup and his family good-naturedly embellished the story, creating the myth that Shoup embraced the role of Jolly Ol’ St. Nick and fielded several calls from children on the clandestine red phone that night).

The errant call that evening should have been the end of the matter, except that a few days before Christmas, one of Shoup’s staff drew Santa and his sleigh on the big board. Aware of CONAD’s unpopularity with much of the taxpaying public for seemingly being in a perpetual state of war, Shoup, with General Partridge’s approval, instructed his public-relations officer, Colonel Barney Oldfield, to contact the nation’s wire services with a story: “Santa Claus Friday was assured safe passage into the United States by the Continental Air Defense Combat Operations Center which began plotting his journey from the North Pole early Friday morning. . . . CONAD will continue to track and guard Santa and his sleigh on his trip to and from the U.S. against possible attack from those who do not believe in Christmas.” The story was enthusiastically received throughout the nation and its readers fully expected CONAD to repeat the Santa story the following year, which it did.

The errant call that evening should have been the end of the matter, except that a few days before Christmas, one of Shoup’s staff drew Santa and his sleigh on the big board. Aware of CONAD’s unpopularity with much of the taxpaying public for seemingly being in a perpetual state of war, Shoup, with General Partridge’s approval, instructed his public-relations officer, Colonel Barney Oldfield, to contact the nation’s wire services with a story: “Santa Claus Friday was assured safe passage into the United States by the Continental Air Defense Combat Operations Center which began plotting his journey from the North Pole early Friday morning. . . . CONAD will continue to track and guard Santa and his sleigh on his trip to and from the U.S. against possible attack from those who do not believe in Christmas.” The story was enthusiastically received throughout the nation and its readers fully expected CONAD to repeat the Santa story the following year, which it did.

So, that’s how the “NORAD Tracks Santa” program began, Cold War-style. Over sixty years later, NORAD (the North American Aerospace Defense Command that replaced CONAD in 1958) still operates the Santa tracker with the help of more than 1,250 U.S. and Canadian military personnel who respond to tens of thousands of calls and emails each Christmas Eve. Its child-friendly website, with videos, games, music, and stories in eight languages, receives tens of millions of hits each Christmas from around the world. Despite criticism from some over the militarization of Santa, the program has become one of the most successful military public relations campaigns ever, and has been copied by Google and almost every local TV station with Doppler radar, providing joy and anticipation to young children each Christmas.

Though I probably should end this Christmas tale there, I am compelled to spread a little humbug on your holiday cheer. Hence, I will leave you with one final thought dancing in your head: Although Sears is closing stores faster than Santa’s elves can shine their pointy ears, and the atheistic Soviet Union is presumably no more, NORAD may soon have to gear up once again to protect Santa from another familiar foe from the 1950s—North Korea.

PHILIP JETT is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder That Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty. Jett now lives in Nashville, Tennessee.