by Alice Sparberg Alexiou

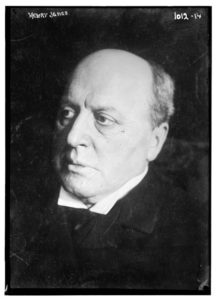

In 1904, at the apex of his career, Henry James came home from Europe for the first time in more than 20 years. He’d written many books—Daisy Miller, The Wings of the Dove, What Maisie Knew, Portrait of a Lady, The Golden Bowl—about his favorite subject: people like himself, genteel ex-patriots who’d embraced the luxury and ambiance of the Old World. He had looked at every facet of his obsession with Americans living abroad, and rendered their nuances into his gorgeous but often infuriating prose, with its too-long, overly embedded sentences. This was the idiom of an American writing in English, and living on the Continent. But now, James, back in the rude, fresh New World, had a whole new angle for viewing his compatriots.

He spent one year traveling around the States, giving lectures and taking lots of notes. The resulting travelogue—The American Scene, published in 1907—showed James with his famously keen eye, searching restlessly for a place in his native land to hang his hat. He’d been away for so long that you could hardly call him American anymore.

James was born in 1843 in New York to an old moneyed family. The city that he remembered from his childhood, with its gentle blocks of brownstones punctuated by the occasional church spire, was being overwhelmed by modern technology. Steel-frame structures reached to such afore-unheard of heights that a new word had to be coined for them—skyscrapers—and a brand-new underground train system was whisking people up and down the spine of Manhattan. Everywhere, buildings were being torn down and new ones erected; the noise was unbearable. Moreover, there were some five times more people living on Manhattan Island in 1904 than when James was born. At that time, the population increase came mostly from immigration, as hordes of impoverished foreigners poured through Ellis Island every day, and from there into the streets of the Lower East Side, making it the then-most densely populated place on the planet.

James was overwhelmed by the changes; and it was the immigrants, with their strange ways and babel of tongues, that most unnerved him. He fretted over what the word “American” even meant anymore: Immigrants, he agonized, are changing the very meaning of American-ness, the concept that has consumed him throughout his life. He was 61 when he returned to America in 1904. But at the same time, immigrants fascinated him; he tried to stop thinking about them, but he couldn’t. So he surrendered to his curiosity. The best place to observe the foreign-born, he discovered, was along the Bowery, that wide, shabby and most New York of thoroughfares (It was sooty, too, thanks to the El that screeched and roared over it, all day and night, in either direction.) The Bowery belonged to the city’s poorest denizens. On and around it, the residents—the vast majority of whome were foreigners—lived, worked, and played. James liked to observe them by riding along with them in the streetcars that traveled “the crepuscular, tunnel-like avenues that the ‘Elevated’ overarches,” as he wrote in The American Scene, p.122.

“Face after face, unmistakenly, was ‘low,’” he remarked. He added that the charm that you associate with, say, Italians when you’re among them in their native country vanished when they became denizens of New York. Clearly, the Italian presence in New York—it was largely with their sweat that the New York subway tunnels got excavated—clashed with his gauzy fantasy-vision of a rich American ex-pat in Italy, a place he adored and used extensively in his writings. As for the Jews, then pouring out of boats every day by the thousands as refugees from pogroms in Russia, they offended him much more than the Italians. Walking through the clogged streets of the Lower East Side one summer evening, he marveled at how crowded it was, and, in addition, how much each denizen’s inherent Jewishness was concentrated to such a degree in each individual. The scene brought to his mind worms, creatures that, when cut into pieces, each “wriggles away contentedly and lives in the snippet as completely as in the whole. So the denizens of the New York Ghetto, heaped as thick as the splinters on the table of a glass-blower, had each, like the fine glass particle, his or her individual share of the whole hard glitter of Israel.”

Good god, Henry James, why did you have to deploy your sublimely crafted prose in the service of such awful thoughts? But like a moth drawn to a flame, he kept returning to the Bowery and the Lower East Side to observe Jews. No surprise, he found great material to write about; indeed, he devoted an entire chapter to the Bowery in The American Scene. The Bowery was lined with Yiddish theaters, and one evening, James dropped briefly into one of them—“a small crammed convivial theatre, an oblong hall, bristling with pipe and glass, at the end of which glowed for a moment, a little dingily, some broad passage of a Yiddish comedy of manners. It hovered there, briefly, as if seen through a spy-glass reaching, across the world, to some far-off dowdy Jewry.” He quickly left, but he later couldn’t get the image out of his mind.

James’ visits to the Bowery corresponded to the golden age of Yiddish theater in New York. Writer Jacob Gordin was penning serious plays for such great actors as Jacob Adler, who spawned an acting dynasty, and the glamorous Bertha Kalisch, both of whom were drawing the attention of uptown critics. Then-culture vulture types were rushing down to the Bowery to see Adler and Kalisch play Shakespeare—in Yiddish—even though they couldn’t understand the language. So popular were both actors that both were offered roles, and played on Broadway, while James was in New York. Adler played Shylock—in Yiddish, since he did not know English—and Kalisch performed in Fedora, in what one newspaper called “her charmingly accented” English.

Uptown audiences were going nuts over these Yiddish stars, and this rankled James, the undisputed master of American letters. The idea of Adler speaking Yiddish, or Kalisch her Yiddish-inflected English—as he snarkily put it, “a language only definable as not in intention Yiddish”—on the American stage felt especially intolerable to him.

Henry James returned to England in 1905. He revisited America only once more, in 1910. He became a British citizen in 1915, and died the following year. He’s one of my favorite authors—I, the granddaughter of some of those Lower East Side Jews whom James was both fascinated and repelled by. And it makes me smile to think of what the great writer would say if he knew that today, “New York” is a moniker for “Jewish.”

Visit our friends at Criminal Element for an excerpt of Alice Sparberg Alexiou’s new book Devil’s Mile, available wherever books are sold.

ALICE SPARBERG ALEXIOU is the author of Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary and The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It. She is a contributing editor at Lilith magazine and she blogs for the Gotham Center. She is a graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and has a Ph.D. in classics from Fordham University. She lives in New York.