by Rachel McCarthy James

by Rachel McCarthy James

Whack Job author Rachel McCarthy James takes a look at how guns, chainsaws, and swords outshined the humble axe as weapons throughout history.

The axe is a humble object; its power lies in its commonality, its everydayness. Throughout its long life, its many uses have been outstripped by tools and weapons with a greater sense of flair and even glamor. Three of these struck me as particular rivals to the axe as symbols of violence, power, and labor: the sword, the gun, and the chainsaw.

Everyone thinks Vikings were super into axes, but they really weren’t–at least more than any other pre-industrial society that needed to make war and lumber. Vikings–like almost every other ancient culture–found swords to be of much higher status.

Swords are more novel than axes, if you use a long enough timescale–the flint handaxe first appeared as long as two million years ago, and the sword emerged as a weapon separate from a dagger around five thousand years ago. The sword is pure weapon–it might be used incidentally for whittling or planing, but that’s not its purpose. The length and relative reediness of the blade are a challenge to shape in one piece, and correspondingly, they’re easier to break and harder to repair. If an axe breaks– handle or blade–it’s not too tough to sharpen, reshape, and repair. Fashioning, purchasing, and maintaining a sword is an investment worth showing off. Plus, there’s the phallus of it all.

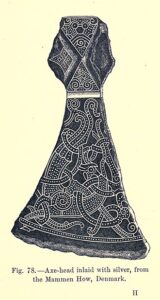

It’s not that axes were never honorable and beautiful. The New Kingdom queen Ahhotep was presented with a beautiful, gold battleaxe by her son Ahmose. A grave dating back to the Viking era found in the Danish village of Mammen contained an iron axe inlaid with silver in intricate yet ambiguous designs of birds and trees that could be in honor of Christian or Pagan imagery. But they are outliers. The axe’s appeal is not in its decorative appeal but its utility: an executioner’s axe can be used to cut wood, a woodchopping axe can be used to behead. Even today, now that neither of them is relevant on the battlefield, the sword still carries a cachet as a decorative object, while the axe is usually put to use by hobbyists.

The gun blew them both away. Firearms date back to ancient Greece, but the ignition wasn’t truly lit until 13th century China, spreading to European warmongers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. As soon as hand cannons and muskets and heavier artillery hit the scene, they took a progressively greater share of military planning and funding. Guns have an ability to obliterate that even the heaviest maul cannot rival.

But as powerful as firearms could be, they were also difficult to use: a hand cannon required an assistant to fire, and while a matchlock could be used by just one person, it was a multi-step process which could blow up in their face. The sword and axe and dagger and spear had just one moving part, and so persisted in war and other forms of state violence through the nineteenth century. Axes were never used in capital punishment in the United States, despite its popularity in English executions; the firing squad was widely used instead, and is still used occasionally today.

As the twentieth century began, bullets became more and more common and accessible, not just for military applications. Civilian ownership of guns skyrocketed. Just as the axe murderer was becoming a headline staple in the 1920s and 1930s, guns were dominating the field of interpersonal violence and especially suicide, a task for which the axe has never excelled.

The axe’s primary occupation has always been woodcutting. And for millions of years, it dominated the field. There were other woodworking tools, but nothing felled trees like an axe. Until the chainsaw.

Industrialization made for a glut of axes at first, when the Bessemer method of steelmaking made it easy to make a lot of steel tools. But as technology advanced rapidly, the axe’s labor applications began to thin out. The chainsaw would bring it to nigh-obsolescence.

A fact as ghastly as any axe murder: the earliest forerunner chainsaw was invented for gynecological purposes. Scottish doctors John Aitken and James Jaffrey, in the late 18th century, invented a flexible saw to be used to cut away at a woman’s pubic bone when her baby was stuck in the birth canal; Jaffrey later added a chain and gears. In the late 19th and early 20th century, its application turned to lumber, fueled by gas and eventually electricity–though like the handcannon the early chainsaw had to be operated by two people. It wasn’t until the introduction of the light chainsaw for home use by a single person in the 1960s that the axe would truly lose its relevance as a common domestic tool.

The chainsaw is unlike the sword, the gun, and the axe (and for that matter, the knife) in that it was never designed as a weapon. It’s a tool, through and through. Ed Gein may have inspired the Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but he never used a chainsaw. They’re better for fictional murders than real ones, because a chainsaw is about as unwieldy and inconvenient as a musket. A chainsaw requires a lot of premeditation, and most murders are not all that well thought out beforehand. And yet it has supplanted the axe not just as a woodcutting tool but as an avatar of violence in cinema and culture, from Leatherface to Limp Bizkit.

The axe is a plain thing compared to the sophistication of the sword, the firepower of the gun, the intricacy of the chainsaw. As the US Forest Manual puts it, it has just one moving part. Flourishes, levers, triggers, these things are unnecessary to the axe in woodcutting and in violence. Its simplicity brings brutal clarity of purpose, a truth to its aim that resonates through the centuries.

RACHEL MCCARTHY JAMES was born and raised in Kansas, the daughter of baseball’s Bill James and artist Susan McCarthy. She graduated from Hollins University in Roanoke, VA, where she studied writing and politics. Her first nonfiction book, The Man from the Train, was written in collaboration with her father and published in 2017. She lives with her husband Jason and pets in Lawrence, KS.