by Glenn Stout

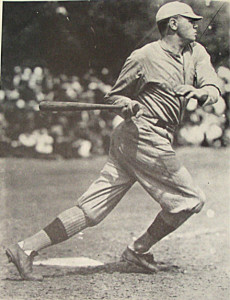

George Whiteman: September 11, 1918

In the eighth inning of the sixth and final game of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs, with the Red Sox nursing a 2–1 lead and only six outs away from their fourth world championship in seven seasons, the Cubs’ Turner Barber cracked a short line drive to left.

Boston’s left fielder, playing shallow, tore in. As the ball sank toward a base hit, he did not hesitate. Instead of playing it safe, he lunged, left his feet, and stretched out for the ball. Bare inches from the turf, he gathered it in two hands, landed heavily, then tumbled, somersaulting over the rough ground, the worn, gray ball still tight in his glove.

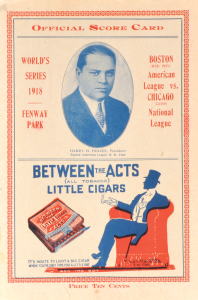

By P. Lorillard Co. Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.com

Barber, visions of heroic headlines evaporating, kicked the dirt and turned toward the Cubs dugout. The crowd at Fenway Park shot to its feet, all 15,238 souls roaring and cheering, slapping each other’s backs and holding their heads in wonder. He had done it AGAIN. The outfit elder rose, threw the ball softly back in to the shortstop, then, grimacing, did not bask in the applause or tip his cap, but twisted his head back and forth and rolled his shoulders as he slowly walked back to his position.

The delay only increased their ardor. For a full three minutes, the crowd cheered as the outfielder tried to shake off the effects of his tumble, bending to clutch his knees and trying to stretch out his neck and upper back. He continued to flex and bend in between pitches as Boston hurler Carl Mays set down the next hitter, but he could not continue and would not risk remaining in the game and maybe costing his team a win, and perhaps even the World Series. He was not that kind of player.

He waved toward the bench and when the umpire held up his hand and called time, started trotting in. The crowd noticed and with each step more of them stood and applauded again, this time with the respect and admiration accorded to a hero. He had been the unabashed star of the Series, his timely hitting— moving runners along, then taking an extra base— sparking several Boston rallies and his glove squelching several Cub comebacks. His selfless removal of himself from the game underscored his contribution; this was a team victory, and here was a man who thought only of his team, and not of himself.

As he approached the Boston bench and manager Ed Barrow rose to greet him, he gave a brief nod to his replacement. Then George Whiteman entered the dugout to the cautious but warm embrace of his fellow Red Sox.

As George Whiteman sat heavily on the bench and Boston’s trainer attended to him, a teammate, almost unnoticed, grabbed his glove and bounded up the dugout steps to take his place, running heavily out to left field. George Herman Ruth had already pitched, and won, two games in the Series, but apart from a few innings as a defensive replacement, had not appeared in the lineup of the other three Series contests, something that had surprised observers at first but also something that George Whiteman’s spectacular play throughout the Series rendered moot. For much of the year, with rosters reduced due to the American entry into the Great War, Ruth, out of necessity, had sometimes played outfield, usually Fenway Park’s short left field, where the earthen embankment known as Duffy’s Cliff and the wall behind it kept spectators from peering in from atop the garage across the street and left the emergency, part-time outfielder little room to cover. As manager Ed Barrow went with the hot hand, Ruth had more or less split time in left with George Whiteman, a thirty-five-year-old career minor leaguer playing his first full year in the major leagues. For much of the season, Ruth had hit far better than anyone expected—in stretches, he seemed like one of the best hitters in the league, and led all baseball with 11 home runs. But he had only hit well in spurts, and over the final weeks of the season he had struggled, particularly against left- handed pitching, leading Barrow to decide to stick with the right- handed bat of George Whiteman in the Series against Chicago’s predominantly left- handed pitching staff.

It was an act of genius. No one realized it yet, but the 1918 World Series was the last quiet gasp of the Dead Ball Era, the lowest-scoring World Series in history, as both teams tried to scratch out runs through a combination of seeing- eye ground balls, short flares, bunts, stolen bases, and hit-and-run plays, punctuated by the rare long hit that rolled between outfielders to the distant fence. The baseball itself, the dead ball, made even deader by the use of inferior wool wrapping and horse hide due to the war, made scoring a premium. Only 19 runners would cross the plate in the six-game Series, neither team scoring more than three runs in any one game, and every man on either team who took the mound during the Series pitched well. It would prove to be the last World Series in history in which no one on either team struck a home run.

The lack of scoring, combined with the distraction of the war and some political misplays by the men who ran baseball, left fans less than enthusiastic. Attendance in the Series had been poor, and on this day, Fenway Park was barely half full for what would prove to be the finale, and the last world championship the Red Sox would win in eighty-six long and frustrating years.

Only George Whiteman had made it seem worthwhile. As veteran baseball writer Paul Shannon wrote in the Boston Post, “In nearly every run the Red Sox scored in the six games, George Whiteman, the little Texan veteran, has figured mightily.” Fans identified with the stocky minor leaguer finally getting his chance to play, the ultimate Everyman underdog, only receiving the opportunity because the real heroes were buried in the mud of a trench somewhere in France. After the Series, George Whiteman’s face would grace the cover of Baseball Magazine, which asked the question “Hero of the Series?????” In his ghostwritten account of the Series, Ty Cobb, the game’s greatest star, would answer that he was.

Ruth? Oh, he played well, too, when he played. Pitching a shutout in Game 1 and then collecting a second victory in Game 4, albeit with relief help after he took the mound with his finger swollen to nearly twice its size due to some mysterious altercation on the train from Chicago to Boston, one that put his fist into contact with either a solid steel wall, a window, or the jaw of another passenger. Although he still set a new record for consecutive scoreless innings pitched in the World Series at 29, one that would grow in stature over the years, it went almost unnoticed at the time.

As George Whiteman left the field that gray afternoon, the spotlight shone only on him, the unabashed star of the Series. Hell, hardly anyone even noticed that Ruth had entered the game. He was upstaged, a bit player in Red Sox owner Harry Frazee’s latest baseball production, standing in for the star as the curtain fell.

It would be the last time.

George Whiteman’s catch left the Cubs with the knowledge this was not their year and they went out quickly. Boston followed, and in the bottom of the ninth, Mays, the submariner and Boston’s best pitcher in 1918, retired Max Flack on a foul. Then Charlie Hollocher lofted an easy fl y to Ruth for the second out. For many fans, it was the first time they noticed he was even in the game.

The crowd stood to witness the final out as Ruth stood before Duffy’s Cliff and watched the Cub’s Leslie Mann bounce a lazy grounder to second base. Forty- year- old Dave Shean, another war time fill-in, fielded the ball cleanly and flipped to first. Stuffy McInnis, foot on the bag, caught the ball with both hands and the Series was over, Boston winning four games to the Cubs’ two.

Another quick cheer rose from the stands, and a few strands of confetti and torn newspapers floated through the air. As the Sox ran in, the other Boston players trotted from the dugout to congratulate each other, but as celebrations went, particularly in Boston, it was muted, more handshakes and hurrahs than screams of joy and dancing in the street.

Although the Red Sox won the World Series, the endless war in Europe, an emerging outbreak of Spanish influenza, an abortive player strike that delayed Game 5 and caused fans to heckle the players with calls of “Bolsheveki!” combined with chess-like play had kept the crowd down and interest in the Series low. Even the Royal Rooters, Boston’s famous group of rabid fans that had followed professional baseball in Boston for nearly three decades, failed to make their usual appearance. After the final out, there was not so much a celebration as a collective sigh of relief that the most trying season in memory was finally over.

About the only player already looking forward to the 1919 season was Ruth. He raced in from left, clutching his mitt in his gigantic hands, ready for a party whether his teammates wanted one or not. While the 1918 season had been something of a disaster for most of baseball (and, despite their victory, even for the Red Sox), Ruth had a great time anyway. Hell, he almost always did.

He might have been a forgotten man at the end of the 1918 season, upstaged by a minor leaguer who would never play another inning of major league baseball. But never again. Over the next two years, the twenty-three-year-old pitcher many newspapers still referred to as George would thoroughly transform himself, the fortunes of two teams, and, most importantly, the game of baseball itself, ushering the sport into the modern era. Ruth, whom the papers had started calling by his nickname, “Babe,” often still placing it in quotation marks, would become THE BABE, the greatest name in the game and the most dominant figure in American sports.

He sprinted to the infield as if he already knew it, as if it was already Opening Day, as if he already could see what lay ahead.

He couldn’t wait…

GLENN STOUT is the author of THE SELLING OF THE BABE The Deal That Changed Baseball and Created a Legend, as well as series editor for The Best American Sports Writing and a Casey Award finalist author of such titles as Red Sox Century, Yankees Century, and Fenway 1912.