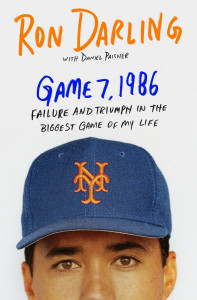

by Ron Darling with Daniel Paisner

Game 7, 1986: Be careful what you wish for

This book is not like other sports books. Certainly, it’s not like other books by former ballplayers. Athletes seem to want to write about the times they beat the odds, dominated their opponents, run the table. They write about their victories, just, and if they spend any time at all on their disappointments, it’s only to make their victories loom larger still. Nobody writes about the times they’ve fallen short, but to me that’s what’s most interesting about this one game 7, at the butt end of this long, sick, wondrous season.

For whatever reason, I didn’t have it that night at Shea, nearly thirty years ago. I’d had a solid year, and my two previous starts in the series had gone well enough, but there was nothing left. I’d written this story a thousand times in my head, but in the end my pitching line told the story instead:

IP H R ER BB K

3.2 6 3 3 1 0

As I consider these numbers, I’m torn. I was never the sort of athlete to congratulate myself on a job well done. I was the last person to revel in my accomplishments. Never once did I kick back and think, Hey, I pitched a great game! There was always something I could have done differently, something I could have done better, and on this night there were a whole lot of those somethings. I don’t mean to give away the story just yet, but there are no surprises here: I left the game in the top of the fourth, after hitting Dave Henderson to start the inning, coaxing Spike Owen to fly to right and allowing my opposite number, Bruce Hurst, to sacrifice Henderson to second. We were down 3-0 and it was as if I’d let the air out of the stadium. The contrast between the crowd I left and the crowd that greeted me as I took the mound for my warm- ups was startling. Top of the first, I’d never seen the Shea faithful so pumped. The place was rocking! But it didn’t take long for those savvy New York fans to see I wasn’t as sharp as I’d been earlier in the series, or for the ruckus to die down on the back of that shared realization. They were still with me in the end— I don’t think there was a single boo in those 50,032 tightened throats as I left the field— but the few cheers that came my way felt more like pity than appreciation. Those kind enough to cheer felt sorry for me, I think— glad to be rid of me, to be sure, but sorry just the same.

Going in, I worried about my control. I’d walked five Sox batters in Game 4, so it felt to me like these veteran hitters were stalking me, waiting patiently at the plate like the cheetahs I’d watched on those Mutual of Omaha Wild Kingdom shows as a kid. Just lurking in the batter’s box, ready to pounce the moment I left the ball up in the strike zone, as if they were calling me out.

Even the elements messed with my head. We’d had all kinds of momentum, coming off that come- from- behind, extra inning win in Game 6, but after a rainout on Sunday night, October 26, that momentum had leaked away. That extra day allowed the Red Sox to breathe and regroup, leaving me and my Mets teammates with a little too much time to consider how close we’d come to calling it a season.

Advantage: Boston.

And here’s another thing: the way we’d come from out of nowhere to win Game 6, the way the Red Sox collapsed when the game was in their grasp, it left a lot of people in our clubhouse thinking we were somehow meant to win this World Series. I didn’t feel that way— not one bit. But that’s a dangerous perspective, if you allow it to take hold.

That extra day left me with all that time to think, and by Monday night, after going through all my pregame rituals a second time, I was a bundle of restless energy—an agitated, unfocused mess. It was a mess of my own making, let’s be clear, but there it was, and even though I managed to pitch my way through the first inning allowing only a single to Bill Buckner, I knew this wasn’t going to be my night. The ball felt heavy in my hand.

Sure enough, when Dwight Evans and my old high school rival Rich Gedman led off the second with back- to- back home runs, you could see my shoulders sag and my false swagger slip away. I felt like Charlie Brown out there on that mound— spinning ass- over- teakettle, my jersey torn from my back by the breeze of those balls off the bats of the Red Sox hitters, a kick me! sign stitched to where my name was meant to be.

I left game 7 with my head held low— the picture of defeat. But we were not done just yet. Somehow, as baseball fans will surely recall, my teammates kept battling. Sid Fernandez came on in relief and held the Red Sox scoreless for the next while, allowing us to catch our own few breaths and put Boston’s momentum on pause. We tied it in the sixth, and went ahead on a Ray Knight homer to lead off the seventh, and from there we scratched and clawed our way to another few runs and held off a Red Sox rally in the eighth and managed to win 8-5— erasing, for the moment, the sting of my early- innings failure.

Here again, I don’t mean to give away the ending, but I’m assuming most baseball fans know the outcome of game 7. They know, as I now know, how the sweetness of that World Series victory would surely linger, but for me it became a bitter sweetness. Over time, the bitter could never quite detach itself from the sweet, leaving me to wonder, over and over, what might have been. Leaving me to think what it meant to dream only blue-collar dreams.

Ron Darling is an Emmy Award-winning baseball analyst for TBS, the MLB Network, SNY, and WPIX-TV, and author of Game 7, 1986: Failure and Triumph in the Biggest Game of My Life. He was a starting pitcher for the New York Mets from 1983 to 1991 and the first Mets pitcher to be awarded a Gold Glove.

Daniel Paisner has collaborated with dozens of athletes and public figures on their autobiographies and memoirs, including “I Feel Like Going On,” with NFL great Ray Lewis; and, “Chasing Perfect,” with Hall of Fame basketball coach Bob Hurley.