by Doug Wilson

The First Baseball Strike in History

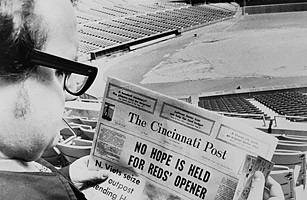

April 1, 1972 baseball owners and the Major League Baseball Players Association played the cruelest April Fool’s Day joke of all on fans. Only it wasn’t a joke. They stopped the game. They shut it down. Never before in the 103-year history of professional baseball had the game, and it’s fans, faced a work stoppage due to labor discord. It was the first baseball strike in history.

Trouble had been brewing ever since 1966, when the Player’s Association had hired 48-year-old attorney Marvin Miller, a former big gun of the United Steelworkers Union. There had been a threatened strike in 1969 but few thought they would actually go through with it. Why would they? Players should have considered themselves lucky to do what every red-blooded male in the country would have done for free–play baseball for a living. Owners appeared to be making money–everyone should have been happy with the sport that was indisputably the national pastime.

Image is in the public domain via dougwilsonbaseball.blogspot.com

But as the scheduled Opening Days of April 5 came and went with empty ballparks still locked up, fans were left on their knees, pounding their fists in the sand, screaming, “You maniacs! You blew it up. Damn you. Damn you all to hell!”

In 1972, the major league minimum salary was $13,500 and the average was $34,092. Carl Yastrzemski was the top dog, still working on his unprecedented 3-year/$500,000 deal. Most major league players worked winter jobs to help make ends meet. Even the stars relished the chance to get an endorsement deal to add extra cash. Players lived in small towns back home, in unassuming houses, in real neighborhoods. In short, they were just like everyone else.

Club owners were upset about losing ground in the past few bargaining agreements. The big issue for 1972 was an increase in pension funding and players’ health benefits, but the real cause was player solidarity. As the deadline for signing a new Collective Bargaining Agreement approached, the owners vowed to hold the line and back the union into a corner. While they knew they would lose short-term cash if games were cancelled, they felt they would make it back in the long term if they could break the union.

Team meetings were held all over the league. It was not an easy decision. Team reps worked to convince the higher paid stars to stick with their lower paid teammates for the common good. Players voted overwhelmingly to support the first baseball strike if needed. Owners were betting that players would cave and crawl back; that players with such widely differing incomes would never stand together. They appeared to have seriously underestimated the players’ resolve.

For players, the first baseball strike was scary. Most players wanted to play baseball and they didn’t know how long their money would hold out.

Image is in the public domain via RealClearSports.com

It was with great rejoicing almost two weeks later when a deal was finally signed. Players ended up being out from April 1 to April 13; a total of 86 major league games were cancelled. Buried at the end of the articles announcing the happy occasion was the fact that part of the agreement stipulated that none of the postponed games would be replayed and that players would not be paid for the missed games. It was a seemingly insignificant detail–but would turn out to have huge consequences for at least one divisional race.

Fans showed their resentment by staying away. Average attendance dropped 10,000 a game for some teams throughout the season. The fans who did show up for games voiced their displeasure with boos for the players, particularly for the leaders of the first baseball strike. But, for the most part, the boos were limited to the first few games. Otherwise, once the games started, the strike was forgotten–until the last week of the season, when the missed games cost the Boston Red Sox the chance to win the pennant.

Read more about baseball’s next epic strike in 1981 here

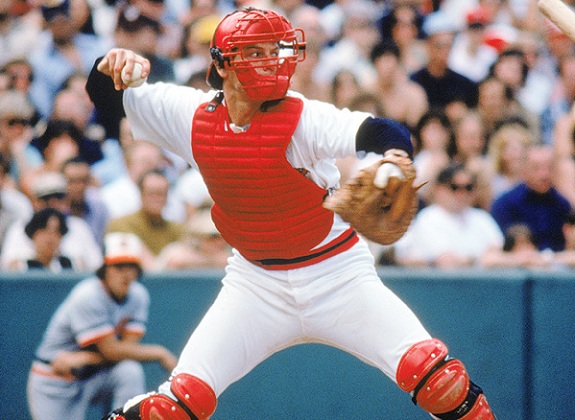

The Sox were a team with a lot of talent, but they had started slow due to injuries and slumps to key players. The Red Sox were carried through the first half by the unexpected Rookie of the Year season from their catcher, Carlton Fisk and the emergence of Cuban pitching ace Luis Tiant. The team caught fire in August and climbed into contention, battling the Tigers of fiery second year manager Billy Martin.

As the final week of the 1972 season approached, it was noticed by observers that there could be no tie. Due to the fact that some teams had more games cancelled than others, the Tigers would play 156 games, the Sox 155. As luck would have it, the Red Sox pulled into Detroit for the final series with the standings looking like this:

Boston: 84-68

Detroit: 84-69

Image is in the public domain via ASSOCIATED PRESS

The Red Sox had to win two of the three games to win the East Division title.

Monday, October 1, 1972, the Red Sox faced twenty-game winner Mickey Lolich in front of more than 50,000 fans. The Sox threatened early, but a base-running error cost them the chance to run Lolich out. He worked out of the jam and proceeded to throw a complete game, striking out 15, while giving up 6 hits, 5 walks and 2 hit batters and won the game 4-1.

The next day the Tigers scraped across a run against Tiant and added two off of reliever Bill Lee and won 3-1. The Sox won the last meaningless game. The final results were:

Detroit 86-70, .551

Boston 85-70, .548

Among the cancelled games had been five head-to-head contests between the Tigers and Red Sox, three of which were in Boston. The Red Sox, and their fans, will never know what would have happened.

Although Commissioner Bowie Kuhn publicly stated that there were no winners in the first baseball strike, it was obvious that the players were the big victors. While the missed games cost a player making around $20,000 a year about $1,100 and guys higher on the pay scale close to $10,000, the loss had been worth it. With the agreement to conclude the first baseball strike, the owners agreed to add $500,000 to the players’ pension fund and, more importantly, agreed to add salary arbitration to the Collective Bargaining Agreement. Arbitration was a huge victory for the players. Now there was a process, in front of an independent judge, which would allow players to resolve contract disputes with owners. This unprecedented move would prove fateful for owners, and their beloved reserve clause, within four years.

More important that any gain made in the agreement was the fact that the players had shown the resolve to bargain collectively, to stick together. As stated by UPI writer Fred Down at the time, it was starkly evident that a “new and fundamental relationship now exists between the players and the club owners.” Baseball, and salaries, would never be the same.

DOUG WILSON is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research and has written three previous baseball books including PUDGE: The Biography of Carlton Fisk. An ophthalmologist by day, Wilson has been a life-long baseball fanatic. He played baseball through college; however, his grade point average was higher than his batting average and he was forced to go to medical school to make a living. He and his wife, Kathy, have three children and live in Columbus, Indiana.