by Art Garner

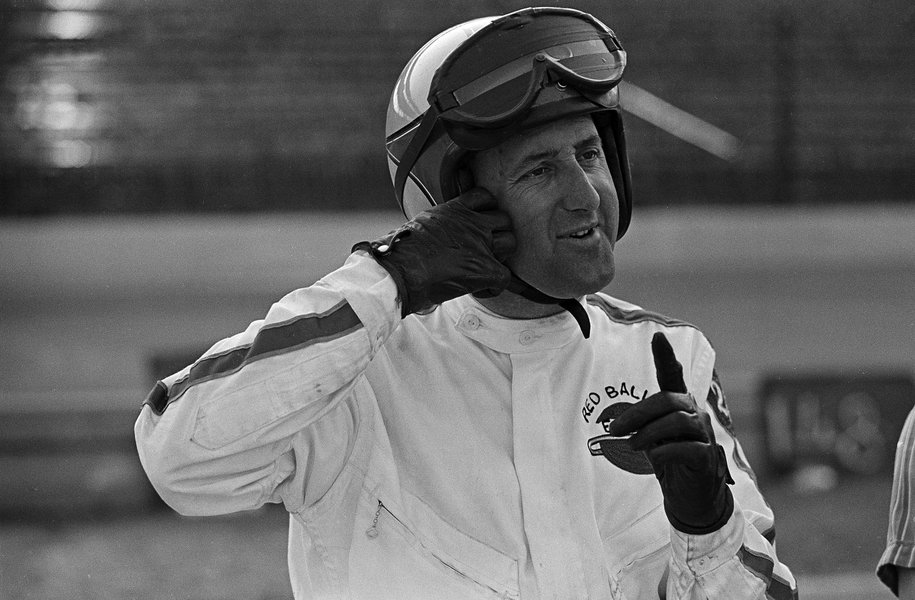

Eddie Sachs: A Curtain of Smoke and Flames

“He really embraced it, made me feel at ease,” Mario Andretti remembered. “I never forgot that about Eddie Sachs. He was a real ambassador for the sport and made an instant fan out of me.”

Benson Ford held the Mustang pace car at a steady 90 mph as he drove through the fourth turn and toward the start/finish line. Although the speed for the pace car was increased for the 1964 Indy 500 race, many drivers still felt it was too slow, given the top speed of the racers.

Once the pace car pulls into the pits, the responsibility for pacing the field falls to the pole sitter, and Jimmy Clark kept it slow as the Mustang moved off the track. The Lotus team was confident their four- speed gearbox, compared to the two- speeds in the other cars, provided them with a significant advantage on the starts and restarts, so the slower the pace, the bigger Clark’s advantage.

As a result, it was a tightly packed and nicely formed eleven rows of three approaching starter Pat Vidan. Compared to the typically ragged start of today’s race, with the field often stretching from the start/finish line through turn four, the thirty- three cars in 1964 were grouped between the flag stand and the entrance to pit road as Vidan, wearing a white sport coat and perched on the pit wall, unfurled the green flag.

Clark timed the start perfectly, working his way through the gearbox as he jumped to a one-, two-, and then three- car-length lead as the field streamed past the starter. Starting fourth, but on the inside of the second row, Parnelli Jones was doing his best to stay glued to the rear of the dark green Lotus. Foyt dropped low, trying to follow Jones through, but Bobby Marshman was also intent on getting to the bottom of the track, forcing his way between the two roadsters and already looking for a way around the defending champion. Rodger Ward and Dan Gurney, from their outside starting positions on rows one and two, moved low and fell into line.

The inside line is the fastest way through turn one. Never, in the history of the 500, had anyone other than the pole sitter led the race into the first turn. However, as drivers farther back in the field jostle to reach the inside, an opportunity arises to gain places on the outside. Because the outside lane provides less traction, it’s a move only for the experienced and courageous, and the opportunity lasts only until the cars are up to speed.

Still, there are positions to be gained for those brave enough and talented enough to take the risk.

This was especially true in ’64. The first two rows were off to a clean start, falling neatly into line at the bottom of the track. The same couldn’t be said for the third row. While Lloyd Ruby stayed with the leaders from his inside third- row spot, Len Sutton, in the middle, and Don Branson, on his outside— two traditional roadster drivers making their first starts in rear-engine cars— were lagging behind. Starting on the inside of the fourth row, rookie Walt Hansgen went by Sutton low while Jim Hurtubise, starting directly behind Sutton in the middle, saw a small gap to the outside and went for it, squeezing between Sutton and Branson. Drivers fighting for position were now running three and four wide as they approached the first turn.

The two other rookies starting up front, Dave MacDonald and Ronnie Duman, both moved to the bottom of the track.

Not surprisingly, Eddie Sachs followed Hurtubise to the outside, moving in front of Johnny Rutherford. This was fi ne with Rutherford. He wanted to follow the veteran Eddie Sachs during the early laps of the race anyway. With Hurtubise several car lengths ahead and no one else in the high groove, Eddie Sachs and Rutherford carried their momentum well into the first turn, surging past Duman and Dave MacDonald in the process.

Clinging to the inside of the track was Bobby Unser. As the field began to bunch up in the first turn, Unser, his hands clenching the steering wheel at seven and two, dropped the Novi low, lower than anyone else on the track, until all four wheels were below the white safety line.

Right where he wanted to be, “Don’t have a wreck, don’t have a wreck,” he kept telling himself. “I can beat these guys. Just gotta wait. Be cautious. Don’t have a wreck.”

Clark was taking full advantage of the open track and the Lotus’s transmission, clipping nearly ten seconds from the record for the opening lap.

Both Marshman and Ward passed Jones on the back straightaway, and by the second lap Gurney was past Jones and Foyt. The rear- engine Fords were in the first four positions and already pulling away. Another Ford was on the move, MacDonald re-passing Eddie Sachs and Rutherford low on the track between the first and second turns as they started lap two.

“Whoa,” Rutherford thought. “He’s either gonna win this thing or crash.” For a moment he thought MacDonald was going to spin and wondered why the rookie was running so hard, before answering his own question.

“That was the way Davey drove. He was a charger and he would try and go to the front and be the leader.”

Whether it was the slow start, the bunched cars in front of him, a Thompson handling better than expected thanks to a full load of fuel, or just the surge of adrenaline the green flag creates, MacDonald was flying.

Next in his sights were the rear- engine Offys of Branson and Sutton, along with the roadster of Dick Rathmann. He passed all three before the fourth turn to move into tenth place. Th e pace was frantic, Clark setting another record as he completed the second lap, the leaders beginning to spread out.

As Clark approached the first turn, MacDonald exited the fourth and was closing fast on Hansgen, who in turn was closing fast on Hurtubise.

The daring move to the outside by Herk in the first turn had allowed him to leapfrog seven spots at the start, but now the two rookies in rear- engine machines were rapidly gaining on him, showing no respect for the roadster.

MacDonald moved first, edging his car to the left to pass Hansgen as they started down the front straight. A split second later Hansgen made the same move on Hurtubise, forcing MacDonald to veer left again.

Then MacDonald lost control of the red Thompson. Dick Hensley, a fireman stationed along the track’s outside wall, was watching the approaching cars coming out of the fourth turn as he was trained to do, one of the few not mesmerized by the leaders now entering turn one.

“MacDonald came through the fourth turn with two other cars,” Hensley said. “As he came off number four he cut to pass. Then the front end of his car lifted at least 1 to 1 ½ feet off the ground. It looked as if the wind just hit him.”

In an instant MacDonald’s car turned a full 180 degrees and was sliding backward and broadside toward the inside wall. He had the front wheels turned in full opposite lock and the brakes jammed in a desperate attempt to slow his car. At the last moment he turned and glanced at the rapidly approaching wall.

Although the rubber bladder holding the Thompson’s gasoline was on the left side of the car and the impact was on the right, the force of the collision tore the neck of the bladder from the refueling cap, shooting a stream of gasoline across the car and onto the hot exhaust pipes. Th e gasoline immediately ignited, engulfing the car in flames.

The inside wall at MacDonald’s point of impact slants back toward the track, and his car ricocheted off it, toward oncoming traffic, fully aflame.

The force of the collision threw his car to the left another 180 degrees, and the nose of the car was briefly headed toward the outside wall. The right rear suspension, destroyed in the initial impact, dug into the track, pivoting the Thompson yet again, the herky-jerky movements sloshing more gasoline onto the fire. MacDonald was sliding backward across the track once more, drawing a curtain of orange flames and dense black smoke behind it.

Close behind MacDonald when he lost control were the three drivers he’d most recently passed, Branson, Sutton, and Rathmann. Sutton’s first thought was that Hansgen must not have seen MacDonald. The three veterans never hesitated, staying in the natural high groove coming out of the fourth turn and running fl at out as they dashed past the sliding and burning car. Sutton glanced over to see MacDonald sliding directly for him—but then he was past.

They were the last of the lucky ones.

Coming onto the front stretch and closing fast was Eddie Sachs, followed at two car lengths by Rutherford and Duman, running nose to tail. Unser was another car length back.

“I was just settling in behind Eddie Sachs to see what developed,” Rutherford said. “I saw a cloud of dust coming off the fourth turn and then a flash of red, a red car. It was sideways off the track. Then it just exploded.”

Eddie Sachs was on the brakes, bunching the four cars even closer. By now they could all see the fire on the inside of the track and a burning car sliding back across it.

Rutherford “had my brake pedal buried to the bottom, just trying to slow down and figure out how to get through that black and orange curtain, knowing there was a car sitting in there somewhere— and trying to keep from running over Eddie Sachs.”

Unser, perched high in the Novi’s cockpit, had the best view. “The whole track was blocked with fire,” he said. “I didn’t know if it was one burning car or ten. It looked like ten.”

In the split second available, all four drivers reached the same conclusion. There was no time to stop.

Rutherford could see the fluorescent red ball on Eddie Sachs’s helmet darting frantically from side to side, searching for a way around the burning car. At the last moment, Eddie Sachs made a move to the left. He never had a chance.

Art Garner is the author of Black Noon: The Year they Stopped the Indy 500. A journalism graduate of Michigan State University, ART GARNER has developed a writing and public relations career that has intertwined with motorsports for more than 35 years. He has worked as a public relations executive at Ford, Toyota, and Honda, through which he has attended races at virtually every major, and not so major, track in America. He lives in Palos Verdes, CA.