By Greg King and Penny Wilson

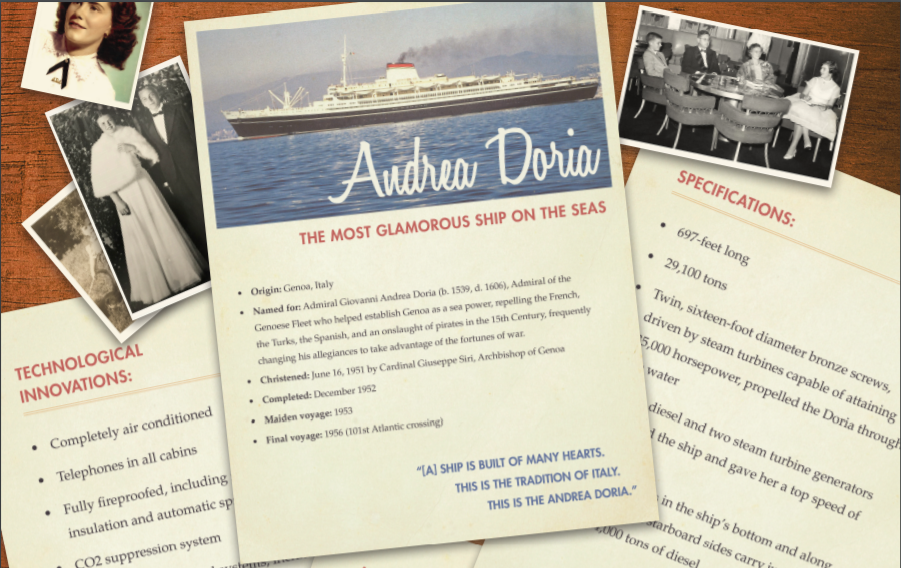

Take a trip back to the 1950s with authors Greg King and Penny Wilson, as they discuss the menu served on the glamorous Italian ocean liner Andrea Doria.

One of the most interesting aspects of researching our book The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria: The Sinking of the World’s Most Glamorous Ship, were the glimpses we got into the daily life and culture of the 1950s. Of course, a liner like the Andrea Doria would have been a microcosm of all that was best and most enjoyable about life at the time; and as eating well and dining in beautiful surroundings have always been part of the pleasure of being alive, we were especially interested in the array of menus we found.

The menu covers were themselves works of art, showing mostly watercolors of flowers indigenous to Italy, including the Edelweiss, perhaps the best-known of Alpine blooms. In a couple of cases, though, the menu bore a cover showing an undersea landscape of colorful fish, ribbon seaweed and starfish. The selection of this art for the menu covers continued both the maritime and Italian themes of the ship itself.

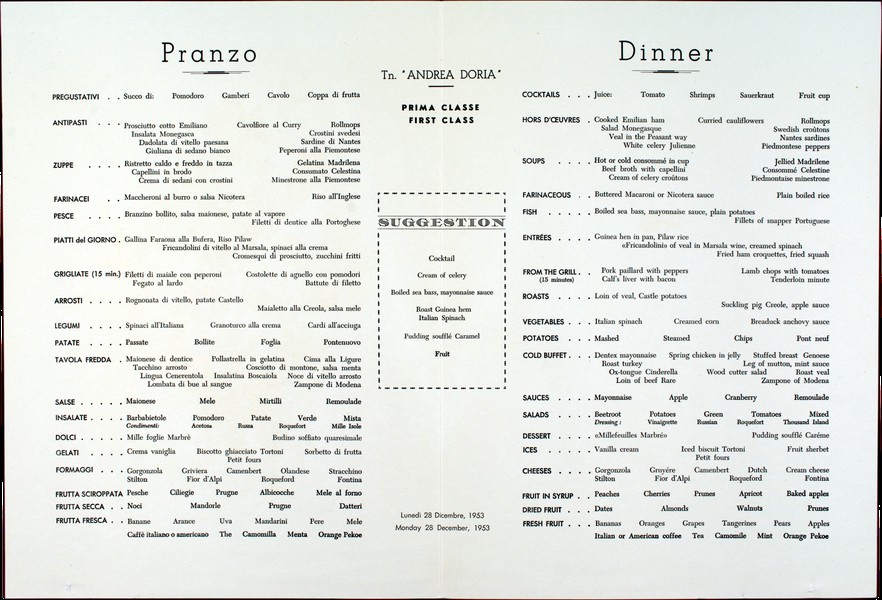

Turning our attention to the dinner menu, we notice that it was laid out with many more selections to be made than a modern restaurant menu might offer. This is the first clue that fine dining almost seventy years ago could have been a much more individual experience, with each person able to customize dishes closer to their own tastes.

For example, while we would likely categorize rice, potatoes, and pasta together as “carbohydrates” or “starches,” one of which might be expected with each entrée selection on a modern menu, the Andrea Doria menu combines rice and pasta under the category of “Farinaceous” (meaning rich in starch) and potatoes have their own category. Macaroni comes buttered, or in a Nicotera sauce, which we are told is a curried tomato sauce with spinach and mushrooms, which sounds delicious – and we are amused to see that what is listed as “riso all’Inglese” on the Italian side of the menu is but “plain boiled rice” on the English side.

We recognize mashed potatoes, steamed potatoes, and even chips – but pont neuf potatoes is not something we see regularly on modern restaurant menus. It seems that pont neuf potatoes are steak fries – short, thick, stubby cuts of deep-fried potatoes also sometimes known as Parisian potatoes. And from elsewhere on the menu, Castle Potatoes are potatoes cut and roasted in the oven, sometimes with olive oil and sometimes with goose grease.

Underneath the potato offerings, the Cold Buffet starts off with something called Dentex Mayonnaise, which proves to be a large, voracious, predatory Mediterranean fish, so-called for his fearsome teeth. It is a delicious fish, and here it is served with a mayonnaise sauce, which we might avoid today for reasons of calories.

Wood Cutter Salad may simply be a coarsely chopped vegetable salad, but it seems to have fallen off the radar in recent decades and doesn’t seem to have an internet presence. Neither does Ox Tongue Cinderella, though some recipes for various vegetables “Cinderella” suggest that it might be a simple ingredient (in this case an ox tongue) all gussied up with herbs, sauces, and dressings.

“Life is short,” someone once said, “eat dessert first.” Turning our attention to the dessert part of the menu, we see that it includes easily recognizable items such as coffee, tea, ice cream, and fruit – fresh, dried and in syrup. The cheeses are all familiar to us with the exception of “fior d’Alpi,” which is described by Waitrose as a medium-strength gently spicy hard Swiss cheese made from cow’s milk.

Check out an excerpt of The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria here!

The millefeuilles Marbreo is a flaky pastry layered with cream and topped with a marbled fondant icing in vanilla and chocolate – very much like the cream slices we bought at cafes in the UK – rich, sweet and satisfying. And a souffle Careme would be a small and traditional souffle made in the style of the nineteenth-century chef Antonin Careme, which is something very close to the manner in which souffles are served today. Careme would have been a familiar name to the classically trained chefs aboard the Andrea Doria. Recognizing that passengers would be a very captive audience once on the high seas, the Italian Line knew the avenue to keeping them content and enjoying their time aboard was best reached through their stomachs. It was therefore essential that the staff of the restaurant and galley be of the highest possible quality.

Of the sixty or so kitchen staff employed on board the Andrea Doria, most of them would have been educated at the Istituto Marino Boccanegra in Genoa. As trans-Atlantic travel became not only more popular, but more obviously time away from daily life which could be enjoyed by the passenger and exploited by the shipowner, various shipping lines recognized that a world-class “hotel” had to be installed on every ship that plied the oceans. In 1926, the Italian Line exploited an already existing school and paid the Istituto to add a three-year ocean-going course which would include training voyages on ships around the Mediterranean so that the students would become accustomed to adapting to the features of working in a smaller and more restrictive ship’s kitchen.

So good was the Istituto Marino Boccanegra’s reputation that over ninety percent of its graduates found employment in the finest hotels and on the finest ships in the world. But in 1957, just months after the Andrea Doria sank, the Istituto was merged with other similar schools into the Marco Polo Hotel Institute, and the training changed radically, focusing on turning out general crew members and hotel staff rather than a range of kitchen-qualified experts.

It is easy to conclude that any of us would have been able to make tasty and enjoyable selections from the menu of the Andrea Doria, though some of the items appear under strange or outdated names. We have a somewhat different relationship with food than did many people seventy years ago, eating for pleasure, yes, but also eating for health. Of course, the kitchens and galleys of the Andrea Doria carried almost no processed and artificially preserved foods, and chemicals in food were virtually non-existent at this time. Having endured food shortages throughout the recent World War, and having had various “substitution” foods like chicory and margarine thrust upon them, most people were desirous of a return to pre-war standards and expectations. The Italian Line certainly stepped up to that mark, and many survivors – particularly those who were children then – recalled the delicious and resplendent lunches and dinners served to them by the caring hands of the Andrea Doria staff.

Greg King is the author of more than fifteen internationally published works of history, including Twilight of Empire. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, Majesty Magazine, Royalty Magazine and Royalty Digest. He lives in the Seattle area.

Penny Wilson is the author of Lusitania with Greg King and several internationally published works of history on late Imperial Russia. Her historical work has appeared in Majesty Magazine, Atlantis Magazine, and Royalty Digest. She lives in Southern California with her husband and three Huskies.