by Alice Sparberg Alexiou

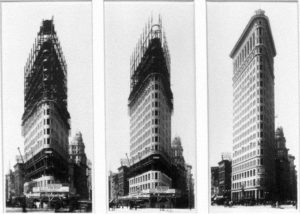

Critics hated it. The public feared it would topple over. Passersby were knocked down by the winds. But even before it was completed, the Flatiron Building had become an unforgettable part of New York City.

The Flatiron Building was built by the Chicago-based Fuller Company–a group founded by George Fuller, “the father of the skyscraper”–to be their New York headquarters. The company’s president, Harry Black, was never able to make the public call the Flatiron the Fuller Building, however. Black’s was the country’s largest real estate firm, constructing Macy’s department store, and soon after the Plaza Hotel, the Savoy Hotel, and many other iconic buildings in New York as well as in other cities across the country. With an ostentatious lifestyle that drew constant media scrutiny, Black made a fortune only to meet a tragic, untimely end.

In The Flatiron, Alice Sparberg Alexiou chronicles not just the story of the building but the heady times in New York at the dawn of the twentieth century. It was a time when Madison Square Park shifted from a promenade for rich women to one for gay prostitutes; when photography became an art; motion pictures came into existence; the booming economy suffered increasing depressions; jazz came to the forefront of popular music–and all within steps of one of the city’s best-known and best-loved buildings. Keep reading for an excerpt of The Flatiron.

* * * * *

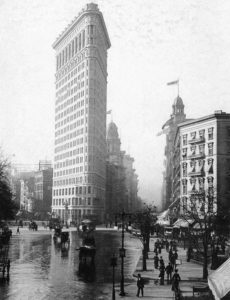

What a clever simile, of a Flatiron building rolling along the sidewalk! How apt, and how iconic! It was precisely the Flatiron’s fluid nature—from every angle, it looked different—that made people love it so. The building embodied New York, where every day people arrived from across the sea, or from the farms of rural America, swelling the city’s population, and continuously remaking the city into something else, that kept evolving with each successive wave of new immigrants. New York, the Evening Post had recently declared, was a “fluid city.” It had not yet been able to settle down, either industrially or socially. New York as yet had no zoning laws—the first would be enacted in 1916—which meant that any quarter could change suddenly into something else entirely.

Change was the essence of New York, and the Flatiron was part of that change. It looked different from any other skyscraper. If you were walking toward it on Twenty-third Street, going west, it seemed like Schuyler’s huge theatrical screen, rising straight up in front of you. If you were north of the building, on Fifth Avenue or Broadway, the Flatiron appeared to be moving towards you, like a big ship. Perhaps you would imagine that it had just arrived from Europe, filled with immigrants, plowed right through the harbor and was now continuing its journey, on land, uptown. “It’s just like a great wedge of strawberry shortcake, with windows for berries,” one young girl was overheard saying. “A tall thin wedge of a building, for all the world like a slice of a gigantic layer cake, a boarding house slice, very thin and tapering,” wrote The Brooklyn Eagle. A Times reporter, watching a man walking down Fifth Avenue with his girl, heard him trying to persuade her that the Flatiron Building was architecturally superior to L’Arc de Triomphe on the Champs-Elysées, and just as beautiful as the Washington Monument on the Potomac. Nonsense, she replied; to her, it resembled a clothespin that fastened Fifth Avenue and Broadway jointly onto the clothesline of Twenty-third Street. Her boyfriend replied: “Granted its scale, it is architecturally well designed. It will be to the travelers on the two great highways of our metropolis a column of smoke by day, and by night, when the interior is lighted, a constellation of fires.” She said, “The Flatiron will probably be used to advertise electrically a patent for weak backs and sore feet.” “But there is something spirited and commanding in it,” persisted the young fellow. “It gives an accent to the vista of two great thoroughfares.”

“But the accent,” his girlfriend said, “is so very American.”

That remark, the reporter later commented in his article, “was taken as a complete justification of the Flatiron Building, for what greater virtue can native architecture have than to be conceived and executed in the native vernacular?”

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, applauding the current and unprecedented popular interest in architecture caused by the Flatiron Building, wrote: “No amount of approval or disapproval on the part of a few interested and competent people can compensate for the (up-to-now) widespread lack of interest in architecture. An architect’s design must appeal to a lot of people, not just the elite. And this can only have a good effect on popular taste. No art can be thoroughly wholesome in a democracy that has not a good basis in popular taste.”

ALICE SPARBERG ALEXIOU is the author of Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary. She has been an editor of Lilith magazine and written for The New York Times and Newsday, among others. She is a graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and has a Ph.D. in classics from Fordham University. She lives in New York.