We teamed up with the Unknown History podcast on Quick and Dirty Tips to bring you their latest series based on Giles Milton’s Checkmate in Berlin. Episode 8 discusses General Alexander Kotikov, a person Western allies in post-war Berlin had never encountered the likes of—a staunch communist with a velvet touch.

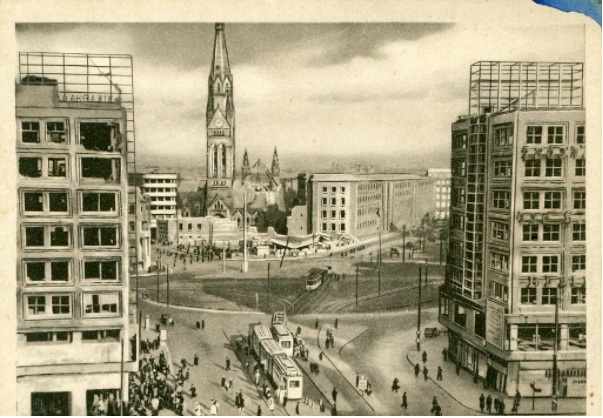

Photo use under Creative Commons license.

Frank Howley had grown used to expecting the unexpected in Berlin, but even he was taken by surprise when he attended a meeting of the Kommandatura at the end of April 1946. The Russian team had undergone a radical purge. Lieutenant-General Smirnov had disappeared without a trace, never to be seen again, and his deputy had been removed due to “terrible stomach wounds received during the war.”

The new and incoming team was headed by a pugnacious heavyweight named Gen. Alexander Kotikov, instantly recognizable by his mesmerizing eyes, his quiff of silver hair, and his blunted turnip of a nose, the latter being the result of his having been kicked in the face by a horse when young.

Howley knew nothing about General Kotikov when he first pitched up in Berlin and was unaware that he had been selected by Moscow because he could be trusted to punch hard and low. He was also a committed Communist. At the age of fifteen, he and his friends had ripped off their baptismal crosses as a gesture of solidarity with Lenin’s Bolsheviks. “By this act,” said Kotikov, “we were joining the revolution.” It was the beginning of a blood-and-guts adventure that would see him fight the Nazis at both Moscow and Leningrad before taking part in the capture of Berlin.

Kotikov was unusually gregarious for a Soviet general and had a flamboyant charm that was wholly absent in the other members of his team. His Berlin office was furnished with an impressive rank of ten telephones, the most striking of which was made from gleaming white Bakelite. “It might have belonged to a Hollywood actress,” remarked journalist Karl Schwarz. “It wasn’t quite like what I had expected a Communist general’s office to be.”

Kotikov was still an unknown quantity when introduced to his three Western-allied colleagues. He certainly made a favorable impression at his first Kommandatura meeting, addressing his fellow members with courteous charm. “I’m new here to the Kommandatura,” he said. “You, my colleagues, are doubtless more familiar with this question. Won’t you let me have your words and advice on the matter?”

Howley came close to being won over, but the fact that such words were coming from the mouth of a Soviet official gave him pause. Over the days that followed, he began to wonder if Kotikov was actually a master of dissimulation, sent to Berlin because he “was an expert on conference technique.” This was indeed correct. Kotikov was a highly skilled operator who outclassed all who had come before him.

“In striking contrast to his predecessors,” said Howley, “he brought a new dialectical weapon to the Kommandatura. He was the first to use humility, and use it effectively.” He would feign ignorance, “begging the speaker to expound more fully, please.” Howley soon saw through this deceit and immediately took against him. “His humility was as unctuous as Uriah Heep’s and, being as serpentine, was as poisonous as a sting.”

Yet he remained captivated by Kotikov. It was as if this were the enemy he had wanted all along, a tough-playing fullback whose role was to expel the Western allies from Berlin. His gregariousness only added to the allure: Kotikov was to prove a most fulsome host, throwing lavish soirees at which the vodka flowed as swiftly as the River Don.

“Well[,] we’ve worked, we’ve talked, now let’s eat,” he would roar as he led the others into the adjoining banquet room. American journalist Curt Riess was witness to one of these feasts. Riess was no stranger to excess, but Kotikov’s lavish entertainments outclassed those of everyone else. “Along the whole length of an enormous table stood the slender towers of bottles: vodka, red Crimean champagne, sweet wines, French cognac, Pilsner beers. There were bowls of Strasbourg pâté de foie gras, roast chicken, game, huge glass bowls of red and black caviar. There were lobsters, oysters, turkey with truffles, every imaginable fish, salads, salmon, sturgeon, and mountains of white bread and butter.”

In the midst of the banquet was Kotikov himself, “the personification of jollity,” who repeatedly slapped everyone on the back as a sign of hearty goodwill. By the end of the banquet, the entire room (with the exception of Kotikov himself ) was completely drunk. “Apparently, alcohol did not affect him.”

Frank Howley was convinced that Kotikov had been dispatched to Berlin for a specific mission. “From the volume of notes he carried and his generally aggressive attitude, it was obvious he had been sent by Moscow with definite orders to get the new Communist party going.” Not only that, but he was also there “to control Berlin and to harass the Western allies.”

To learn more about the history of World War II, visit Unknown History on Quick and Dirty Tips. Or, you can listen to the podcast below.