By Stephen Grey

Chapter 1: Captain Francis Cromie and the Cult of Intelligence (1909-89)

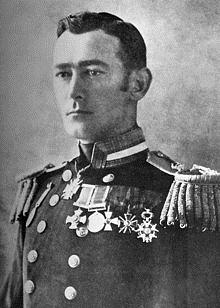

Captain Francis Cromie – thirty- six years old, tall and strongly built, a commander in the Royal Navy and bearer of the Distinguished Service Order – reached into the consul’s drawer and pulled out a revolver. It was 31 August 1918, a day when Russia was at a crossroads in its history. It was also Captain Cromie’s last day alive. Captain Francis Cromie was in the British Embassy in wartime Petrograd (St Petersburg) and it seemed that the ‘Red revolution’ of workers and peasants’ communism was in jeopardy.

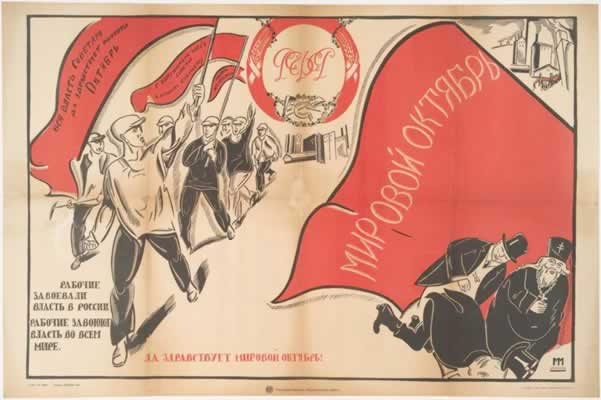

A day earlier, Moisei Uritsky, the local chief of the new secret police, the Cheka, had been murdered in cold blood. Now word came through that, 400 miles away, the leader of the Reds, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, had been shot too. He was in bed in the Kremlin with two bullets inside him, one in his chest and one in his neck, and surgeons were unclear if he would survive.

Further north, British and other allied troops had landed on 4 August in the town of Archangel to join the White Army – the combined anti- revolutionary forces. Though this allied force consisted of only 5,000 men, more were expected, and the Bolsheviks feared that they would be marching south. There was word too that inside the city foreigners were conspiring with ultra- left revolutionaries and former tsarists to mount a counter- coup against the new revolutionary government. These rumors were true and one of the plotters was Captain Cromie, a man of action and an intelligence officer. With other British secret servants then in Russia, he was tangled up in the West’s first trial of strength with the new communist power. The events of those epic days, and the errors made, would define modern espionage. Just after 4 p.m., witnesses at the embassy heard shouts and the slamming of car doors in the yard outside. The Cheka had arrived. Captain Francis Cromie was busy holding a council of war in the chancellery with fellow diplomats and several spies and hangers- on. But he had been betrayed. Two of his trusted contacts in the room, Lieutenant Sabir and Colonel Steckelmann, who claimed to be part of the tsarist White Russian forces, were in fact Cheka agents.

In another part of Petrograd, a British intelligence officer – the man the public would later know as ‘the ace of spies’, Sidney Reilly – was waiting to meet Cromie. He was hoping that a coup against the Reds he had fomented was about to be launched. According to an eyewitness, as recorded in the British National Archives, a member of the Red Guards – the armed volunteers of the Bolshevik revolution – approached the chancellery door with a revolver. Cromie turned to his companions and said, ‘Remain here and keep the door after me.’ He then opened the door, leveled his gun and shouted, ‘Clear out, you swine’, before heading down the passageway, pushing the Red Guard before him. No one saw what happened next, but during an exchange of fire in the corridor two of the raiders were shot.

Cromie sprinted down the corridor and out on to the chandeliered grand staircase. As he leapt down its carpeted steps, the Cheka agents, already upstairs, chased after him, firing down from the balcony. Two bullets penetrated the back of his skull and he fell in a heap at the bottom of the stairs. He groaned softly, his blood draining into the carpet. Captain Cromie had become involved with fellow British spies in a bid to overthrow the Bolsheviks, but they had been outwitted and compromised. He was perhaps the first man to die because of a blunder by officers of His Majesty’s Secret Service.

Stephen Grey, author of The New Spymasters and Ghost Plane, is an award-winning investigative journalist who has contributed to The New York Times, 60 Minutes, ABC News, CNN, Newsweek, The Atlantic Monthly, the BBC and other publications.