by David McKean

President-elect Franklin Roosevelt liked William Bullitt the moment they met. Bullitt was energetic, clearly intelligent, and there was a bold, dashing quality to the forty-year-old former diplomat that attracted Roosevelt, an immensely charismatic figure himself.

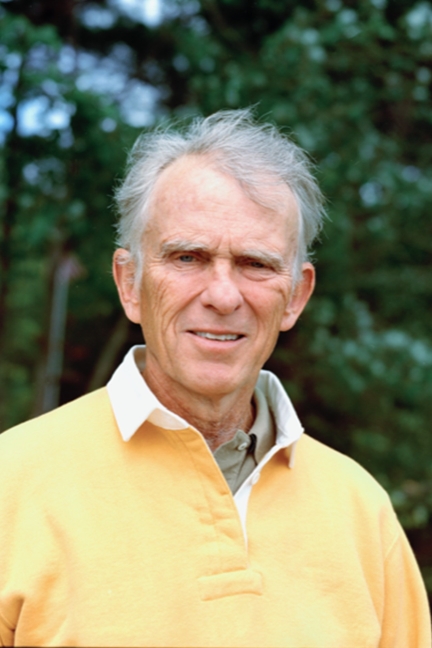

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Bullitt hailed from a prominent family in Philadelphia. He attended Yale and, like Roosevelt, had served in the Wilson Administration. Indeed, Bullitt, when only twenty-eight years old, had been tasked to negotiate with Vladimir Lenin on establishing diplomatic relations with the Bolshevik regime.

Roosevelt would certainly have known of Bullitt before making his acquaintance. After negotiating with Lenin, Bullitt had resigned from the Peace Commission in Paris and returned to the United States; he then broke with President Wilson by publicly testifying before the U.S. Senate against ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, which he viewed as a flawed attempt to bring peace to Europe. Roosevelt may have also been aware of Bullitt’s 1926 novel, It’s Not Done, which was a best-seller, outselling F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

As he prepared to take office in March of 1933, Roosevelt wanted a foreign policy briefing. A longtime supporter, Louis Wehle, the nephew of Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, arranged the meeting with Bullitt. By the end of the evening, Roosevelt had decided privately that he would find a place somewhere in his administration for Bullitt, and in December, after the United States established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, Bullitt became the United States’ first ambassador to the communist state.

Before his departure, however, Bullitt began an affair with President Roosevelt’s loyal and beloved personal secretary, Missy LeHand. According to James Roosevelt, the president’s son, Bullitt had been “the one big romance” in Missy’s life, but “Bill treated her badly.” Bullitt, who had been married twice before, was undoubtedly very fond of Missy, but he also relished the access to the president that his relationship with Missy afforded him.

Bullitt arrived in Moscow with high expectations that the U.S.S.R. and the United States could work together. His initial dinner meeting with General Secretary Stalin and Soviet leaders was filled with elaborate toasts to friendship between the two countries. At the end of the evening, the two men embraced.

But relations quickly turned sour as Moscow reneged on its promises to pay reparations and Bullitt increasingly witnessed the brutality of Stalin’s totalitarian state.

Notwithstanding the dissatisfaction he felt in dealing with the Soviets, Bullitt made a number of friends among the city’s intelligentsia. In 1934, he held an elaborate holiday party at the embassy that was later fictionalized in Mikail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita. In a long letter to the president, Bullitt described the hedonistic affair, though he claimed “no one drunk.” Roosevelt seemed to get a kick out of his ambassador’s antics, writing him that the next time he visited Washington, he wanted to hear all about the “parties in the embassy after 2:00 a.m.”

However, after learning of his ambassador’s frustrating overtures to the Soviet government for debt repayment, President Roosevelt recalled Bullitt from Moscow in early 1936 to help with his re-election campaign. Bullitt wrote speeches and served as an adviser as Roosevelt cruised to victory and a second term in November 1936. The president then appointed Bullitt to the coveted post of ambassador to France.

In Paris, Bullitt quickly gained a reputation not only as a seasoned and savvy diplomat, but as a charming and charismatic host as well. In addition to the grand embassy residence, Bullitt rented the Chateau de Vineuil-Saint-Firmin at Chantilly, an eighteenth-century limestone manor house with a wine cellar that he stocked with eighteen thousand bottles of wine.

In the early months of his posting, Bullitt frequently wrote President Roosevelt that the only way to avoid war in Europe was for Germany and France to reach some sort of political and economic understanding with one another. Bullitt counseled the president to dismiss the American ambassador to Germany, William Dodd, because Dodd had alienated the Nazi government; Bullitt offered up himself as a kind of ambassador-at-large who could smooth relations between the two European powers. During this period Bullitt wrote numerous letters to Roosevelt. Though often incisive, the letters were also obsequious and saccharine in tone: Bullitt told the president that he and Mrs. Roosevelt had made him feel as though he were “a member of the family,” and on another occasion, how “he wished to Heaven he could swim with the president in the White House pool.”

After Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Bullitt completely changed his view of a possible rapprochement between Germany and France and advised the president “to create an army now.” The following year, when Bullitt observed German troops massing along its borders with the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Belgium, he correctly predicted the Nazi invasion of the Low Countries.

Bullitt is perhaps best known for the courage and resilience he showed as the Germany Army advanced to the outskirts of Paris. As the French government evacuated, Bullitt helped to negotiate the German occupation of the city, and is credited by many with having “saved Paris” from destruction.

Bullitt later returned to the United States and beseeched President Roosevelt to appoint him to his cabinet. But Roosevelt had other priorities and balked. The ambassador then grew impatient and somewhat surly – with the president and with his colleagues in the State Department as well. President Roosevelt ultimately bristled at Bullitt’s impertinence and dismissed him from the government. The “champagne ambassador” as he was known in Paris, had a nasty falling out with the man he had once claimed to “love.”

Enter for your chance to win a copy of Watching Darkness Fall by David McKean below!

David McKean is the former US Ambassador to Luxembourg, and former director of Policy Planning for the US Department of State. He is currently a Senior Fellow at The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Washington, D.C.