by John Berlau

George Washington: accomplished general, famous statesman…business innovator? Most people don’t know that Washington was one of the country’s first true entrepreneurs, responsible for innovations in several industries.

As president, George Washington received many requests from ship captains or drivers of horses and carriages for permission to pass through secure areas without interference from the military or other authorities. Most of these requests were routine. However, on January 9, 1793, he granted a safe-passage request from the pilot of a highly unusual vehicle: a new invention called a hot-air balloon.

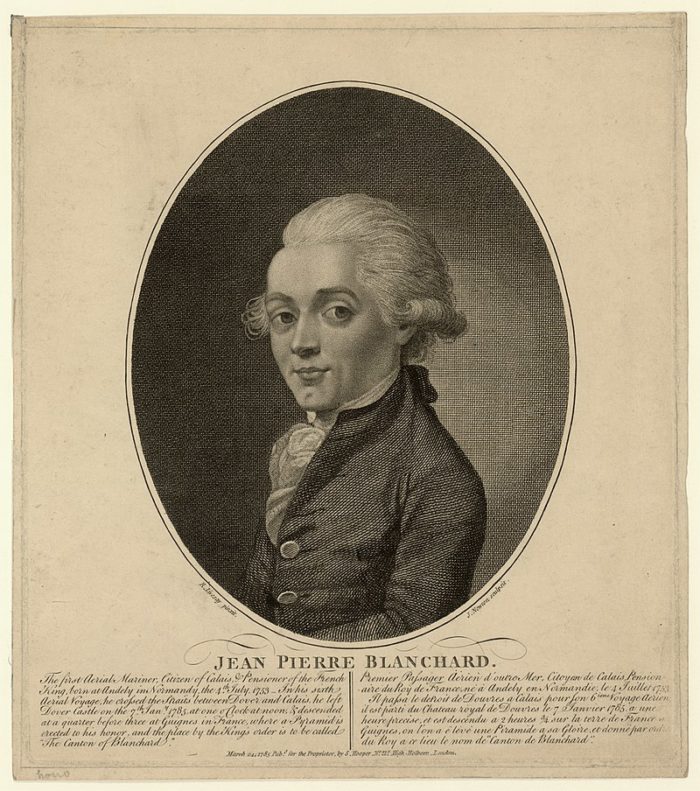

Balloon flights had recently been pioneered by a small number of enthusiasts in Europe, drawing large crowds and causing a widespread sensation. French pilot Jean-Pierre Blanchard had successfully launched short flights in France and England and had also flown across the English Channel. Now he wished to bring his air show to America.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Not only did Washington allow it, he gave the visitor a hearty American welcome. Cannon fire, at regular intervals, awoke the capital city of Philadelphia on the same day Washington signed the letter of safe passage. At 10 a.m., in front of gathered crowds, Washington himself appeared to give Blanchard his pass and make a short speech praising the man he called “the bold aeronaut.” Future presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were also in attendance. After waving the flags of the United States and France to the crowd watching from the street and the windows of nearby buildings, Blanchard took off and covered 15 miles in a then unheard-of 46 minutes. He would return to Philadelphia by conventional travel later that evening to visit Washington and tell him all about the day’s journey.

Washington was already well aware of the phenomenon. The craze had been kicked off ten years earlier, when the first manned balloon flight was launched in Paris by the Montgolfier brothers. The balloon was up in the air for a grand total of 25 minutes, and it traveled just about five miles. The public was fascinated, yet few grasped the implications for the future. Washington was one of those few.

Despite Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that Washington’s mind, though capable of making sound judgements, was “slow in operation, being little aided by invention or imagination,” Washington was quicker than most of his contemporaries to see the potential of manned flight. Writing to French military leader Louis Lebègue Duportail in 1784, Washington made this prediction: “The tales related of them are marvelous, and lead us to expect that our friends at Paris, in a little time, will come flying thro’ the air, instead of ploughing the ocean to get to America.”

In fact, Washington saw the potential of many inventions of the early industrial age, and he gladly served as a mentor or booster for a number of other innovators. He championed inventors both in his policies as president and in his dealings with them as a private citizen.

Believe it or not, when the United States became a new nation in the 1780s, inventors didn’t have the best public image. As Andrea Sutcliffe explains in her history of steam power, many people at that time viewed them as “self-indulgent crackpots.”

Fortunately, these individuals found an ally in Washington, who viewed them as visionaries desperately needed for the growth of the new nation. In his first address to Congress on January 8, 1790, Washington called for the “introductions of new and useful inventions from abroad” and “encouragement . . . of skill and genius in producing them at home.” Congress passed the Patent Act later that year for the purpose (in the Constitution’s words) of “securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

In 1891, speaking at an event at Mount Vernon on the one hundredth anniversary of the Patent Act, Joseph M. Toner, an eminent physician and lecturer who had served as president of the American Medical Association and American Public Health Association, described Washington’s crucial role in helping inventors. He told the audience that “the instances in which Washington gave encouragement to new inventions are numerous,” and that Washington would always have “a kind word of encouragement for those working to the end of devising new methods and improved implements in any of the arts.” As Toner noted, Washington was likely sympathetic to their struggles because he had tried his hand at inventing a few labor-saving devices himself.

In the 1780s, Washington made what he would call a “drill plow” or a “barrel plow” by putting wheels on a plow and attaching a barrel to it. The revolving barrel would carry the seeds he wanted to plant and drop them into small seeding tubes affixed under the plow. The tubes would then distribute the seeds in the field at precise angles. The improved spacing of the seeds led to better growth of Washington’s crops. The plow also helped Washington pursue his longstanding goals of crop rotation and conservation. In what had been the cornfields, Washington’s workers would put different types of seeds in each tube of the drill plow and plant corn, cabbage, potatoes, and peas all in one field with one device.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Nevertheless, by 1797, Washington likely replaced his drill plows—which had limitations on rough terrain— with the new mechanized “threshing machines” he was buying to plow Mount Vernon’s fields.12 Washington’s penchant for mechanical tinkering combined with his knowledge of architecture led him to build unique structures around Mount Vernon to improve the efficiency of his farming. We have already discussed the “dung repository” he designed to preserve excess manure in its liquid form. During his presidency in the 1790s, Washington wrote letters to his Mount Vernon farm managers detailing the construction of a unique, 16-sided barn for grain storage and processing. The barn, completed in 1794 and reconstructed at Mount Vernon in 1996 from Washington’s original plans, contained many unique, practical features. For instance, Washington deliberately left spaces between the floorboards to move the grain via ramps to the granary underneath while horses slowly paced the white oak floor. The design of the barn made the horses part of the grain refining process.

Copyright © 2021 by John Berlau.

Learn more about Washington’s business pursuits:

John Berlau is an award-winning journalist, recipient of the National Press Club’s Sandy Hume Memorial Award for Excellence in Political Journalism, and Senior Fellow for Finance and Access to Capital at the Competitive Enterprise Institute. He is a columnist for Forbes and Newsmax, and has contributed to Financial Times, Washington Post, Politico, Wall Street Journal,and Washington Times. He is a frequent guest on CNBC, CNN, Fox News, and Fox Business. He lives near Mount Vernon in Alexandria, VA.